This is a slightly abridged version of an article written for the Schiller Institute’s Fidelio magazine in July 2013.

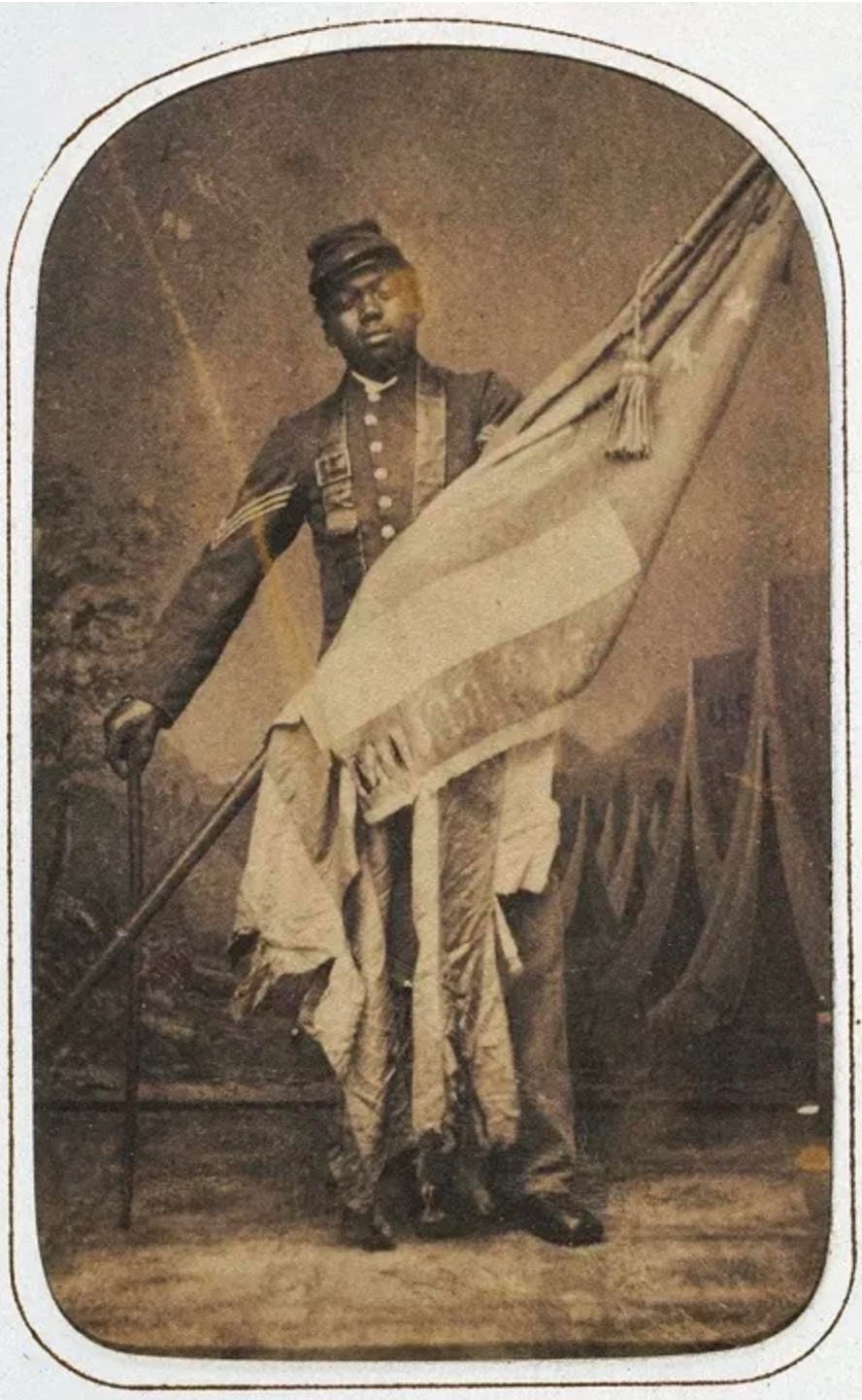

It has been said that the Shaw Memorial by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907) was America's first monument that celebrated the defeat of slavery, and the first American work of art to depict African-Americans as heroes. However, the monument is a bittersweet image, and Saint-Gaudens did not sugarcoat the terrible battlefield losses suffered by this all black, all-volunteer Massachusetts 54th Regiment.

On July 18, 1863, these units endured casualty rates of over 50% in just the first few minutes of battle. They lost their commander, Col. Robert Shaw, but continued to charge into direct cannon and canister fire from the enemy, in the near-suicidal frontal assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina. They planted an American flag on the top of the enemy parapets, but at the end of the day, the fort remained in enemy hands.

President Lincoln saw the reaction, that helped to galvanize the North, and commented that the bravery and determination of these troops changed the civilian population, which made victory much more likely in the future.

Saint-Gaudens captures these proud troops not engaging the enemy, but rather engaging us, the American public.

Across the North and especially in his native New England, Colonel Shaw was viewed as a martyr. In 1865, an African-American businessman in Boston (and former runaway slave), Joshua Smith, proposed a traditional equestrian statue as a memorial to Shaw, and soon other local businessmen joined the effort. They consulted several sculptors including Saint-Gaudens, but Shaw's father insisted that none of them had the right idea. Shaw's father, an Abolitionist, had a long discussion with Saint-Gaudens, saying that his son would demand that the black troops share a position of equal importance in the monument, and if the artists did not understand the significance of this idea, then they could never understand why his son went off to fight.

The elder Shaw insisted that it was critical that the black troops not only appear in the monument, but also each one had to be portrayed as a distinct individual. He did not want a focus on bulging muscles or battlefield bravado, but rather the quiet power of these humble troops to grab us, the viewer, and force us to rethink our role in directing the country.