This is the edited transcript of an interview with former Intelligence official Col. Fletcher Prouty conducted by EIR’s Jeff Steinberg for the LaRouche Connection Public Access TV Program. Fairfax Public Access studios, Fairfax, Virginia. Nov. 10, 1992. Bracketed text, footnotes, and subheads have been added.

A YouTube video of this interview is available here.

Jeff Steinberg: Hello, my name is Jeff Steinberg. I want to welcome you to a very special edition of The LaRouche Connection. Today, it is my great privilege to introduce as our guest for the next hour, Col. L. Fletcher Prouty, a distinguished career military officer and historian, author, and expert on the international railroad industry. Some of you may be familiar with Col. Prouty from his 1970s book, The Secret Team: The CIA and its Allies, which has recently been republished, and is once again available. Of Course, tens of millions, if not hundreds of millions of people in the United States and around the world are familiar with Col. Prouty as the real-life character upon whom the figure of “Mr. X” in the recent Oliver Stone movie JFK was based.

Col. Prouty has recently published a new book, JFK: The CIA, Vietnam, and the Plot To Assassinate John F. Kennedy. It’s a great pleasure to welcome Col. Prouty here to the LaRouche Connection show today.

I thought that it would be sensible, rather than giving a long sort of a curriculum vitae introduction, to ask you to start off by telling our audience a little bit about yourself, your career, because it is so extraordinary and it’s such an important backdrop to the discussion that we’re going to have about your book today.

1943: Chinese Representatives Were Present at the Tehran Conference

Col. Fletcher Prouty: Jeff, I came on duty, actually, as an army cavalryman. I’ve ridden horses as far as 600 miles, day after day [laughs]. I started with that, and then went into tanks. I was on duty before Pearl Harbor. After that I went through flying school. I was based in Cairo Egypt. One day I was asked to pick up a team of people who were going on a trip. They were a geological survey team going into Saudi Arabia to look at the oil fields there during the war. We came back and we found out that [President Franklin] Roosevelt, [UK Prime Minister Winston] Churchill, and [Generalissimo] Chiang Kai-shek were having a conference in Cairo—the Cairo Conference of World War II [Nov. 22–26, 1943]—and that the geological survey people made a report to Roosevelt who immediately ordered a 50,000 barrel/day refinery to be built in Saudi Arabia. That started the big Saudi Arabian oil boom that we’ve seen since then.

When you take part in something like that early in your career, you’re kind of interested in the way things develop. A morning or two later, after the Cairo Conference ended, I was told to get my plane ready. I went out to the plan and they brought the Chinese delegation out there. We flew to Tehran, Iran. I didn’t know what was going to happen in Tehran; I’d just been ordered to fly there.

En route, I stopped at Habbaniyah, Iraq. A plane came in with an old friend of mine flying it and Elliott Roosevelt. I introduced Elliott Roosevelt to the Chinese. But, you know, to this day, you cannot find in a history book that the Chinese were at the Tehran Conference with Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill. I know of one book, printed by the U.S. government that corroborates that. Of course, I have pictures and my co-pilot and crew were there.

Part of the Tehran Conference [Nov. 28 to Dec. 1, 1943] business was to make plans for the Far East after World War II.

So, you begin to think about how these things happen, when they come up like that.

1945: CIA Transfer of Military Equipment from Japan to Korea and Hanoi

I was in Japan at the end of the war. We were bringing the POWs out as soon as we could. I went back to Okinawa where we were based. They were loading ships with this enormous stockpile of equipment that was to be used to support the invasion of Japan: five hundred thousand men, and we didn’t need it.

I was talking with the Harbor Master in Naha. I asked him “What are you going to do? Run that all back to the States?” He said, “Hell no. Half of this is going up to Seoul, Korea, and the other half we’re sending down to Hanoi, [Vietnam].” Half of what we were go use to go into Japan went to Korea and half went to Hanoi. This was Sept. 2, 1945, and those plans were in being at that time.

Who made those plans? Truman had been President for only a few months. I doubt that he did. You know who made the plans for that, because a little later came the Korean War [June 25, 1950 to July 27, 1953]. They used the weapons we sent there. Then came the war in Vietnam [Nov. 1, 1955 to April 30, 1975]. Ho Chi Minh was using the weapons we gave him against the French. That’s why he was able to surprise the French with first class artillery pieces that they didn’t think he had.

1954–65: CIA Operations in Vietnam

Then we reversed the field. We began to back the French, to the extent that we spent $2–3 billion supporting the French against Ho Chi Minh. In 1954, the French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu. Ho Chi Minh inherited all of the arms the French lost, and then, from 1954 until 1965, we were involved in Vietnam, but under the operational control of the CIA, not a military operation.

This gets very important when you see things like that happen. Just think of one problem from the papers all the time concerning he POWs and MIAs. You don’t have POWs when you don’t have an army there. Just because somebody’s working for the CIA doesn’t give them POW status, and so on. All these things get confused in an historical story that doesn’t really make sense.

The first [U.S.] military people who went into Vietnam were the Marines at Da Nang in March 1965, and yet, as John Foster Dulles had said in a speech, himself, we had been in Vietnam since 1945—twenty years in the preparation, you might way, for this war.

Why do I use the word “preparation”? Because some of the things that were done, like this arms movement and setting up the units in Vietnam before we ever had military people there, took 20 years to do that.

Steinberg: You made a point. By the way, I should just interrupt here because I think it’s very important. Some people may be somewhat misled by the title of your book, which talks about the JFK assassination. I think it’s essential to tell people that this is truly an extraordinary history of the entire period of what’s been called the “Cold War,” building up to the Kennedy assassination and beyond.

The question you, yourself, just posed: Who made those decisions? In the very beginning chapter of the book, you used a term that I think was originally coined by Buckminster Fuller, the “international power elite.” You talk, to me in what was very impressive terms, about some of these behind-the-scenes decision makers. You talk about the propaganda schemes that sort of define their world outlook. Maybe it would be worthwhile, as we get into this real history of the Cold War, to perhaps start out by just telling people a little bit about this international power elite and these propaganda schemes, and how some of this thing works.

Col. Prouty: It’s very common for people to respond when you try to speak that way, saying, “Oh well, here’s somebody that just believes in conspiratorial theories, or is a little bit paranoid.” But we ought to stop and think carefully what we’re talking about. All of history has been controlled by powerful figures. [Twice UK Prime Minister Benjamin] Disraeli in the 19th Century said that for those people who are not aware of it, if they do realize what goes on behind government, they wouldn’t believe it.

Sun Tzu, the Chinese Emperor [544 BC to 496 BC], said the same thing back in his period. Buckminster Fuller takes us back 2,000 years, talking about “the elite.” In this country, today, we recognize the power behind, let’s say, lobbyists, who are, in a sense, “above” the government, in that they pay special money to the president to get him re-elected; they pay special money to senators and congressmen to get them re-elected, but to influence legislation in their favor.

There is, and has been, throughout history, an elite that runs countries and the world. What is this one world all about? If we don’t recognize that, it’s very difficult to understand the situation we’re in.

1800s: The Malthusian/Darwinian Worldview of the British East India Company

Steinberg: You make a point several times in the book about the outlook of a British East India economist named Thomas Malthus. You relate his world view to this power elite, specifically to the kinds of things that went on during the peak of the Vietnam War in the ’60s.

Col. Prouty: You see, by that time in history, the British Empire had been built on the control of the sea. They were able to drive ships around the world. They knew the world was a sphere—the flat world had gone out. Knowing that the world is a sphere is a very important thing for mankind. It means its surface is finite, and if its finite, then there’s not more space over there and more there; it’s just so much. So they began immediately to inventory Earth. This was one of the jobs of the East India companies.

Thomas Malthus [1766–1834], who taught at Haileybury College, the East India college, was Director of Economics there. It was his job. He was the first person ever assigned to inventorying the Earth: Where does tin come from; where does iron come from, and so on, and in the process they began to find out how many different people there were in the world; how many different types of people; how many races of people, where everything was. They began to map the world.

Well, that’s a very important function. But it leads you to one more thing that has governed a relationship between countries ever since then. Malthus came up with the idea that the population is growing every so much faster than the ability to raise food, and therefore it wouldn’t be long before mankind would run out of food and there would be a terrible loss of life.

It was very convenient that [Charles] Darwin [1809-1882] came along, working for the same employer, the East India Company, with the idea that, well, life is a race for the survival of the fittest anyway, and so the fittest survive.

Now, those two theories, which are propaganda, sort of made it legal for the people who invaded—the colonialists—to kill off a couple hundred thousand people. First, because “They weren’t going to get to eat anyway; and certainly, they weren’t the fittest, because they’re not alive now, they’re dead. We’re the fittest.” It backed up the idea of this proprietary colonialism that swept the world from that period right up into the 19th Century, and in some respects, applies today. Look what’s going on in Europe. Look what went on in Vietnam, where hundreds of thousands of people were killed, and the feeling was what they called the “mere gook” idea, in other words that it doesn’t matter; they’re not going to live anyway.

It’s a very powerful underpinning to civilization today.

1944: Beginning of the ‘Cold War’

Steinberg: You point out that, in a certain sense, this 30-year American war in Indochina and the whole process of the preparation for the Korean War, then Vietnam, was going on even before World War II ended. It’s quite striking. It seems to me that what you’re saying is that even though in 1944–45, the Soviet Union was still part of the Allied Forces fighting against Nazi Germany and Japan, that we were already beginning to prepare the way for the new war, the Cold War, with communism as the big enemy. Is this an accurate or incorrect assessment?

Col. Prouty: You are correct. In a sense, the beginning of the Cold War is indefinite. But it’s not. You can trace it back. I, myself, as a transport pilot, was asked one day to take about 40 transport aircraft to the north of Syria. The General ordered me to go from Cairo. We were going on the orders of OSS [Office of Strategic Services] people who were in Bucharest, Romania, who, they claimed, had released American prisoners of war [POWs] who were captured in the Balkans. The Germans had just been pushed out of the Balkans and the Russians were on the way in.

So, in the interim, between the two, they brought out about 750 American POWs. They put them on a freight train which they ran through Turkey to the northern border of Syria. We had planes parked there. The men jumped out of the train, climbed into our planes and we started flying them back to Cairo.

I noticed on my own plane there were five or six men who obviously weren’t Americans. They were perfectly willing to talk. I went back and talked with them. They were pro-Nazi Romanians. They were Intelligence specialists who we4re bringing out Intelligence files, not only of Eastern Europe, but of the Soviet Union area.

In other words, here in September 1944, while we were fighting hard as partners of the Soviet, we were already building up a Nazi base of intelligence against the Soviet. I mean, the Cold War was already in motion. It was not Winston Churchill who made the first “iron curtain” speech. It was one of the OSS friends in Germany, von Krosigk, who was then a foreign minister[1] of Nazi Germany who made a speech [May 2, 1945] about an iron curtain, about the Soviets building this curtain over Eastern Europe. That speech appeared in the London Times on May 3, 1945. Churchill read it there, wrote a letter to President Truman, and a year later Churchill’s making a speech out at Truman’s favorite college in Kansas.[2]

Why don’t we take a look at history the way it happened, instead of all these embellishments that are thrown our way. The Cold War started while we were still fighting, and we, in a sense, had allies on both sides: German allies, and we were still allied with the Soviets.

1961: Bay of Pigs Invasion of Cuba

Steinberg: One of the other very critical events in more contemporary history which has been written about at great length but I think has been uniquely presented in your book, both because of your position at the time in the Pentagon, which gave you a particular angle on it, but also because of your subsequent work as an historian. I’m talking about the Bay of Pigs. According to your book, [the event] did not at all occur in the way that most official histories present it today. I’d like you to, maybe, tell our audience a little bit about that because it’s such a critical event.

Col. Prouty: I went into the Pentagon in 1955. The National Security Council had just directed that whenever the United States was involved in clandestine activities, that that clandestine activity would be supported by the military, but managed by the CIA. This is the first time they defined it that way and clearly.

The Chief of Staff Air Force[3] called me in and said, “Look, we want you to set up a global organization to provide the military support that is requested for the clandestine activities of CIA. Now, this got to be a very large organization, because we had operations in Indonesia and Tibet, well, all over the world.

In that capacity, early in 1960, I was approached by two CIA men who told me about the plan that eventually became the Bay of Pigs. It wasn’t called that then, but it eventually became that. They said they needed a base to train Cuban exiles, so we arranged to fly to Panama and we opened up Fort Gulick, a base [in the former Panama Canal Zone] that had been closed. It was a very fine facility, just exactly what they wanted.

The training began at Fort Gulick. We had to provide them with housing, with doctors, and everything else it took to train the Cuban exiles. We then built an airbase at Ritalhuleu in Guatemala, and another one at Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, a big base near Lake Pontchartrain near New Orleans, and, of course, the biggest CIA station in the world in the Miami area.[4] All the time, enlisting Cubans.

By the time of the Presidential election in 1960—Kennedy vs. Nixon—this business of overcoming [Fidel] Castro in Cuba was a very big issue. It’s kind of interesting, because a lot of people concede that [John] Kennedy defeated [Richard] Nixon because of his sense of the Cuban invasion requirement in the 4th debate, when Kennedy said that ought to be preparing ourselves to remove Castro, and Nixon didn’t say anything, as he later said, because he knew the plan was in effect and was highly classified, and he assumed Kennedy didn’t [know about it].

For example, the Kennedy-Nixon debate was October 21, 1960. In August of 1960, again, because of my job, I was sent to Sen. Kennedy’s office in the Senate office building. I had to bring two staff cars over there. In his office were four men—Cubans. They were the head of what became the Bay of Pigs program, one of whom was [Dr. Manuel Antonio] de Varona, and another was [José Miró] Cardona. Manuel Artime was the military commander on the beach. I was there to pick them up. Kennedy knew them. They were already there; they had been talking to each other; Artime’s team had been at his home in West Palm Beach. People think Kennedy didn’t know what was going on, or that he didn’t know the Cubans, didn’t know their aspirations. He certainly did. He knew before many others did.

I brought these four men over to the Pentagon to meet with the Secretary of Defense, who at that time was [Robert] Gates.

But, you see, people attribute to Kennedy a lack of knowledge of this, when really that’s not accurate.

From this beginning, we finally got to the point where a brigade had been formed and trained and equipped to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. The absolutely essential requirement of that attack was that every Castro combat aircraft would be destroyed before the brigade landed at dawn on Monday, April 17, 1961. Now, there were only ten planes. It wasn’t a big deal.

On Saturday morning, April 15th, seven of the ten had been destroyed, but, quite by chance, three T-33 jets, what we call “T-Birds” had flown down to Santiago, Cuba. Our U-2 reconnaissance planes found them that afternoon. On Monday morning, before dawn, four B-26 bombers were ordered by President Kennedy himself to attack those T-33s and destroy them.

This is very crucial, because if those three planes were destroyed, there were no aircraft for Castro’s air force; there would be no requirement for air cover, and all these stories that have developed since then. The facts are that Kennedy, on that Sunday afternoon, when he approved the landings with the proviso that there be this airstrike to destroy Castro’s planes. That’s the critical step in understand the Bay of Pigs. Kennedy did not withhold air cover, or anything else. He followed the plan as it was drawn by a very able Marine colonel[5] and approved by the Joint Chiefs of Staff to destroy all of [Castro’s] combat aircraft.

But they weren’t destroyed. That was the problem.

Steinberg: What happened? Why weren’t they destroyed?

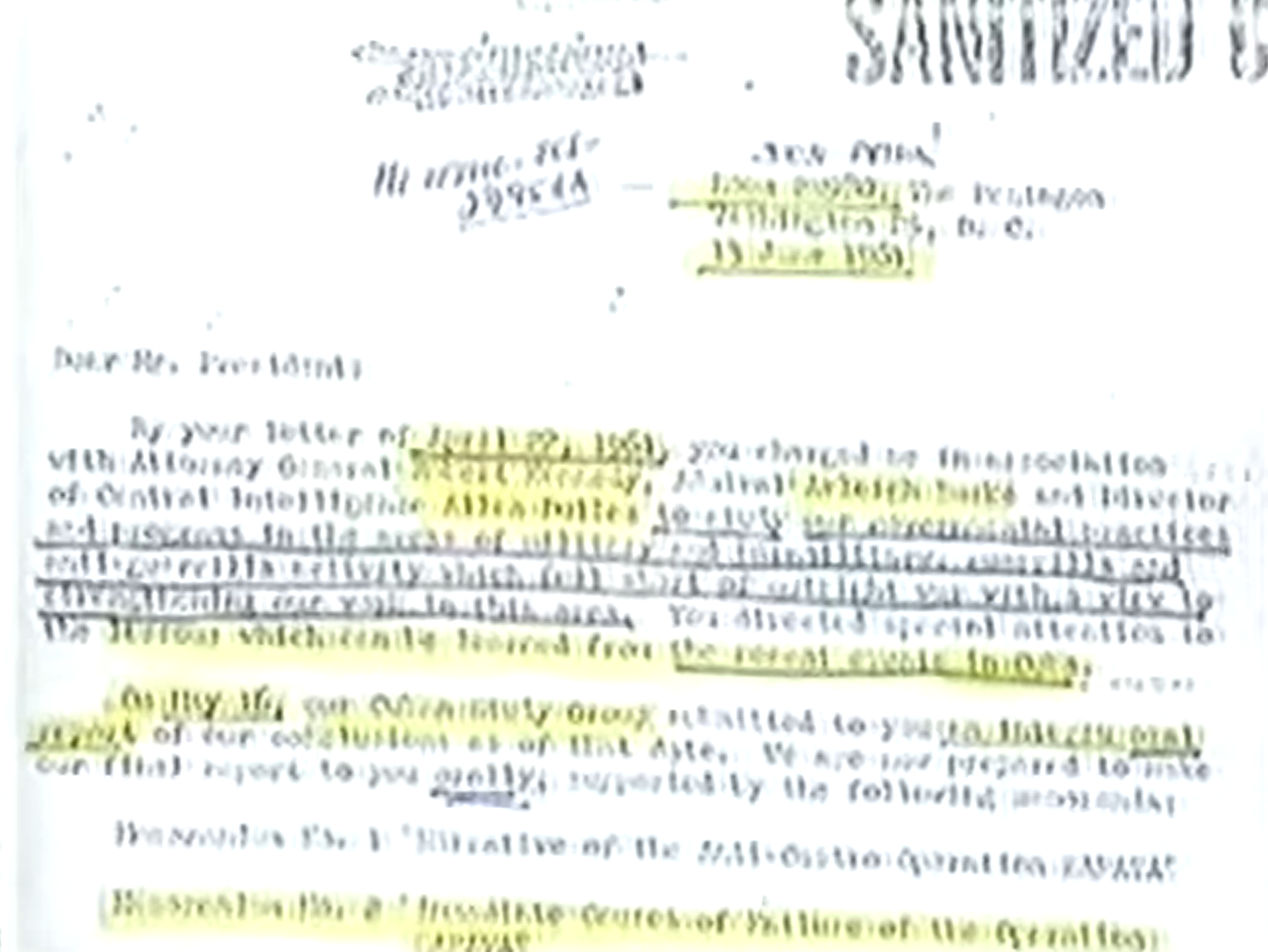

1961: Cuban Study Group

Col. Prouty: Well, this is a bit of history, and it’s contentious, I’ll admit. This document was prepared by the Cuban Study Group, which was assigned by Kennedy the day after the surrender of the brigade on April 22, 1961. The group is very interesting. If you ever could think of four different people trying to work together: Gen. Maxwell Taylor, the retired Chief of Staff of the Army; Alan Dulles, who was head of the CIA, but for some reason or other was not in Washington at the time of the invasion of Cuba; Admiral Arleigh Burke, Chief of Naval Operations, who had had more to do with the Bay of Pigs program than the Chairman had, so Burke was asked to be there; and then the real point of interest in the group, [Attorney General] Robert Kennedy.

Steinberg: Huh.

Col. Prouty: Now, for all their inquiries, they met two doors from my office. The door of their room is listed on their cover letter. The reason I present this is, this is a true copy of the report that Taylor gave to the President. In this report, it states what the Committee came up with as a reason for the failure of the program. I’ll just read it right out of the report, because I don’t want anybody to differ with the way it should go:

“At about 9:30 p.m., on the 16th of April, Mr. McGeorge Bundy, Special Assistant to the President, telephoned General Cabell of the CIA[6] to inform him that the dawn airstrikes the following morning should not be launched until they could be conducted from a strip within the beachhead.”

In other words, after they took the beachhead.

“Mr. Bundy indicated that any further consultation with regard to this matter should be with the Secretary of State.[7] Gen. Cabell, accompanied by Mr. Bissell[8] of CIA, went at once to Secretary Rusk’s office, arriving at about 10:15.”

Now, there’s no sense in going further on that. The entire thing is documented, that the failure to fly that strike is why the thing failed. Further back in the report are the words of Dr. de Varona, who would have been the new president of Cuba, had they won. He said,

“We would be in Havana today if those three jets had been destroyed.”

Now, anybody who writes otherwise, is just misinformed. There [points to the report] are the official papers.

Steinberg: Let me ask you, now: Allen Dulles, head of the CIA, is out of town. McGeorge Bundy, President Kennedy’s National Security Advisor, countermands the military plan for the Bay of Pigs, and as a result of that countermanding, there’s a fiasco instead of a victory. What kind of conclusion do you draw from this? Were their senior people in the Kennedy administration who were consciously out to sabotage this in order to somehow or other weaken the Kennedy Presidency, or what? History generally attributes the failure to John Kennedy, not McGeorge Bundy. But what you’re saying here is extraordinarily important.

Col. Prouty: Well, I think it is. I think it really is. But I think we should also put it in the time. Be very careful. Hindsight doesn’t make a good historian.

The Kennedy administration was new in April of 1960. They had been there February and March. Fairly new. You could not expect that the civilian element of the administration would necessarily have a lot of military experience. As the report goes on to show, some of the people who were briefed about the significance of destroying all the aircraft first, didn’t realize that three little jets, up against a whole fleet of B-26s—we had armed the exiles with B-26s, but they are slower than the jets, so they couldn’t fight them. They didn’t think they would make that much difference.

I’m willing to side with Adm. Burke and Gen. Taylor in saying, as they do further on, that there were misunderstandings; they didn’t understand the tactical problem. Well, we could leave it there. Some people would like to squeeze it up a little tighter and say it was countermanding the President. I think that should be a matter of choice. What I’m interested in doing is presenting the record, and the record says the words I just read. They don’t give a reason, but I’d like you to keep this in mind:

Every day the questions were asked of the people in that room by this committee. Bobby Kennedy left immediately back to the White House in the afternoon, to talk with his brother, the President. Had there been any doubt in his mind, or in the President’s mind that this report that Bundy did on his own isn’t right, they would have stopped immediately and would have said, “Well now, Kennedy told Bundy to do this, or somebody else told him. But there was no one else seeing it that’s silent

So, we have to be a little careful about that, but the record speaks for itself pretty clearly. It was a very bad blunder.

1961: National Security Action Memorandum 55

Steinberg: What happened as a result of that? Kennedy is presented with Taylor’s Cuban Study Group Report. What does he do on the basis of that?

Col. Prouty: Very interesting stuff. Because, in this report is not only the requirement to study the failure, but Kennedy had decided he was not going to rely on the CIA anymore, and that he was going to have to have an alternative system created for the operation of clandestine operations of the United States government. In this report there are the words written by the people in the Committee—by Gen. Taylor primarily—that became one of the most important national security action memoranda ever published by Kennedy. And that’s the highest government our government can published. It is National Security Action Memorandum No. 55, issued in July of 1961.[9]

Essentially, NSSM 55 says that the President holds the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) responsible for advice to him in peacetime operations—meaning clandestine operations—as he would be in wartime. Now, right away, that meant that the JCS was going to be in charge of these things, that the programs would be run by the JCS under the direction of the National Security Council (NSC), and the CIA would not be in clandestine operations. A powerful statement, translated by Sen. [Michael] Mansfield and [Associate] Justice [William O.] Douglas—both friends of Kennedy—that Kennedy was going to destroy the CIA into a thousand pieces.

Well, that’s another way to say it. But what is actually said are the words that the JCS would be responsible for advice, and then they would carry out [the orders of the President]. Also in this report is a long section on what the alternative system would be, when the President was not involved.

Steinberg: Of course, the events at the Bay of Pigs occur at a critical junction in the whole development of the Vietnam engagement of the United States. As you point out throughout the book, the U.S. involvement in Indochina—what you refer to as a “Thirty-Years’ War—began in 1945.

One of the things that was very striking to me was your description of a series of rather significant steps that were taken with U.S. involvement in Indochina: a large relocation of population, some rather significant measures that disrupted the traditional culture and economic infrastructure of the country. What you, more or less, seem to be suggesting, is that these blunders, these actions taken without a real appreciation of the culture of the area, had as much to do with creating the conditions of chaos and warfare in Vietnam as anything else. I’d like you to tell our listeners something about this, because, again, yours is a rather unique vantage point view of what actually went wrong in Vietnam.

Col. Prouty: I mentioned earlier that we had armed and equipped Ho Chi Minh, which would surprise a lot of people now, but that’s how it happened. We then broke away from that and began to arm the French until the French were defeated in Dien Bien Phu in 1954. In 1954, there was an agreement in Geneva that Vietnam would be separated at the 17th parallel into North Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh, and South Vietnam under a question mark for a little while, under Bao Dai, the old king. But very shortly, in about June or July 1954, Ngo Dinh Diem, an exile Vietnamese, was brought in by the United States, and made President of [South] Vietnam in about June or July 1954.

Of equal importance, in January and February of 1954, the subject of what do in Vietnam had come up several times. People should be very familiar with the fact. I very carefully cite this from records: [President Dwight] Eisenhower, in speaking to the National Security Council, said he “bitterly opposed” (his words) the introduction of American troops into Vietnam. He would never approve that. In less than a month from that meeting, the Dulles brothers [Allen and John Foster]; the Secretary of Defense [Charles E. Wilson], and some others, were meeting on what was called the Vietnam Committee of the National Security Council.

1954: CIA’s Saigon Military Mission Begins Vietnam War

They approved an idea that CIA Director Allen Dulles came up with, which was to introduce just five men into Vietnam as, more-or-less, special advisors with the support forces, there to get the country started. As a country, South Vietnam had no existence; it had to get started. Allen Dulles called that unit the Saigon Military Mission, put it under the control of Col. [Edward G.] Lansdale, who had been in the Philippines, and other men.

One of the first things they did was to use the paragraph in the Geneva Agreements that said, apparently in all fairness, any North Vietnamese who would rather ben in the South is free to go, and any South Vietnamese who would rather be in the North is free to go. What the Saigon Military Mission did was go into North Vietnam and, through all kinds of acts—terrorism, propaganda, frightening the people, and everything else—they managed, unbelievably, to cause 1.1 million of those North Vietnamese to move to South Vietnam.

Now, it wasn’t all done quite that simple. U.S. Navy transports carried 660,000. In my book I have photographs of the operation, just so people know what really took place. Civil Air Transport airline, a proprietary CIA airline, carried between 300,000 and 400,000. There’s only one port in South Vietnam. It’s at Saigon. So, the transports have to go down the coast and up the [Saigon] River to Saigon, then turn these million people loose. Can you just picture what would happen if a million people from New York were all of a sudden taken to Kansas City and just dumped loose with no money, no home, no food, no automobile, no TV? What are you going to do with them?

Well, that’s what happened in Vietnam. These people became rioters, they were trying to get food, they didn’t have drinking water. You can be up to your knees all day in a rice paddy, but you can’t drink that water. And so on. A terrible situation came up, such that—you’ll remember the days—the fighting in Vietnam took place south of Saigon, not up in the North. If the Canadians were going to fight our country, would we expect the war to take place in Florida? Well, that’s what was going on in Vietnam.

This was a make-war deal, going back to the Malthusian theory that, well, these poor folks aren’t going to make it, anyway, so if we kill off that million or million-and-a-half, or four million (as was more likely the number), so what? That kind of thinking took place in that country. The war-time fodder, the people who get shot at and chased around, to a great degree, were these million.

Now, in these million were many 5th columnists, put there very alertly by Ho Chi Minh and his forces. That exacerbated the problem. So, when [South] Vietnam came into being with that kind of a problem—

What do you do when you create a country today and you expect it to defend itself tomorrow? No army, no police, no tax system. You don’t create a country in a day. This was another problem. We never really recognized it properly. [President] Eisenhower, himself, in 1954, said we should let the Vietnamese fight their own war. Well, that’s a nice thing to think about, but they had no means of fighting the war. The other man, armed to the teeth with weapons we had brought to Vietnam [back in 1945], was crawling all over them.

We don’t really understand the background history of the Vietnam War. All we remember is that our Marines invaded Vietnam in 1965 and we had 550,000 American soldiers there by 1969 or so. Sure, that was a big war then. But when it’s those first 20 years that I’m talking about—

Another thing is that all of that first 20 years was when the leading operating commanders were all CIA people carrying on clandestine warfare as they had been ordered to do. They didn’t invent; they were ordered to do it, which changes Vietnam history a little bit.

Steinberg: You’re basically saying, I gather, that some of the activity in the South that was generally being transmitted back to the United States on the 6:00 O’clock News as “communist insurgency,” “Viet Cong operations,” and the rest, was a consequence of a chaotic situation, banditry, and these kinds of things, brought about starvation and the policy of mass migration of this million or so people down from the North.

Col. Prouty: Read today’s paper. Read tomorrow’s paper. What’s going on in Yugoslavia? What makes people fight in the streets in situations like that, particularly in Vietnam and back in ’54 and ’55, is hunger. They had nothing. We dumped a million people loose—

Vietnam has a history as old as any part of the world. It is an ancestral ground type society. They never leave ground where their ancestors were. The place where their ancestors’ bones are buried is sacred to them. They don’t jump in the nearest Honda and drive off to the nearest McDonalds. They stay right where they live. And to pick up a million of them and move them down to the South and just turn them loose created a war.

If you remember the geography of the war, when this very famous man, John Paul Vann had been made a General—he wasn’t a military General; he was sort of made a General by the civilians, and not the CIA. It was the aid program, I think[10]—where did they put him to fight? South of Saigon! You see? There’s where the war was then.

And as it went on, it bloomed up into a major debacle. For instance, do you realize that we lost over 5,000 helicopters in Vietnam? Over one-third of the men who died in Vietnam, died in helicopter crashes, helicopter operations, even just in helicopters crashing by themselves. That’s an expensive business.

Steinberg: I think you said somewhere in your book that the cost of the Vietnam war, just in terms of military hardware, was about $230 or $240 billion. On this Vietnam question, was [President] Kennedy actually about to cancel the plans to move U.S. military forces in a large-scale way into Vietnam? Was this an important aspect of why Kennedy was assassinated?

Col. Prouty: As I said earlier, Jeff, you can’t write history with hindsight. So, I would cancel your word “cancel.” Because, in 1960, just to give you a good example, Time magazine mentioned Vietnam six times. That’s how important it was. They mentioned football more than that.

By 1962, we had about 15,000 to 16,000 men in Vietnam, many of whom were the helicopter maintenance people for all these helicopters out there that the CIA was operating, and other logistics people.

By the end of 1962, [Paul D.] Harkins, the General who was out there, asked for more troops. He said, “I got people here, 15–16 thousand, but I don’t have any combat people. General [Earle Gilmore] Wheeler, the Army Chief of Staff at the time and the man who brought me down to the Joint Chiefs of Staff and set up my office there, had a report made of that. They found out than less than 1,600 men were really combat experienced, and that they were training the new Vietnamese army.

That was what Kennedy had when he was making the studies about Vietnam. There were no orders to build up. It was a question of whether, in the future, he would do that.

During 1963, beginning, we’ll say, in August, my own boss, Marine Gen. [Charles C.] Krulak, was in the White House at least 30 times, meeting with [Secretary of State Dean] Rusk and [Secretary of Defense Robert] McNamara, and other leaders, deciding on the policy of Vietnam, all under the close eye of Kennedy. This is all in a wonderful book that the government has published in 1991, on U.S. foreign relations. A recent volume that goes from just August to December 1963. It explains Vietnam better than anything else ever written.[11]

When it finally came time for Kennedy to issue orders about Vietnam, he accepted the report written by the Secretary of Defense, McNamara and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Maxwell. This meant that the Vietnamese now, by 1963, could stand on their own feet, provided we gave them money and weapons, and so on, but we didn’t need troops.

1963: National Security Action Memorandum 263

In that report, NSAM 263[12], it said [among other things] that we’ll bring home 1,000 men by Christmas, and all U.S. personnel out of Vietnam by 1965. You may have seen the picture in my book. I took a photo of the front page of the Army’s own newspaper, Stars and Stripes, which had a banner across the top. People who say there was nothing in history that would prove that Kennedy was saying that is already disproved just by that paper. Other papers, of course, said the same thing: Kennedy was taking American all personnel—it didn’t say just military—out of Vietnam by ’65.

That was Kennedy’s key plan. He was going to run for President again in ’64. He knew he would win and in ’65 he was not going to bring Americans into Vietnam. That’s one of the key things that we made a point of in Oliver Stone’s movie, JFK. We said Kennedy was not going to put Americans in Vietnam.

‘Mr. X’ and Jim Garrison

Steinberg: Let me ask you about that. As I said at the beginning of this interview, many millions of people around the world by now have been introduced to you, at least indirectly, through the character of “Mr. X” in Oliver Stone’s movie, JFK. You were in correspondence and communication with Oliver Stone throughout much of the preparation and making of the movie. Prior to that, you had a correspondence and working relationship with Jim Garrison[13]. Could you tell us a little bit about that?

Col. Prouty: I know that you know that Garrison wrote a book, On the Trail of the Assassins.

Steinberg: Right.

Col. Prouty: Because we had corresponded for years, he sent me a manuscript of his book. I thought the book was wonderful, but it was the story of Miami, New Orleans, Dallas, and it think about Washington, New York, Frankfurt Germany—the money centers. To me, you’ve got to follow the money line.

So, I would write to Jim and say, “Look, the book is good, but we need to put this in, or this. He respected that. Later, sometime, I don’t really know when, we weren’t that close, he was talking with Oliver Stone, who had an idea of doing this movie. In the process, Garrison showed Stone some of the material I had written. Stone called me in July 1990, and said he was going to be in Washington and would like to meet me. He said he wanted me to work as an advisor to the movie he was planning. We met, got along just fine. I told him I agreed to be an advisor and work with him.

Much of the movie material is straight out of my book. The words that you remember from the movie are in my book. That part I had written in 1985. It was already a series of articles that had already been published. The ending of the movie is based on that, where actor Donald Sutherland, who played my part, comes in and talks to actor Kevin Costner, who played Jim Garrison’s part. They begin to describe why Kennedy was killed, not who did it and all that sort of thing, or who’s covering it up, but why was he killed. This is what I tried to answer during that bit of the movie.

Steinberg: I think the movie very much benefitted from that scene, because it gave the audience a chance to get the bigger picture. I must say that as good as I found the movie to be, I think your new book goes much further in terms of elaborating on that critical question, cui bono?

1963: Prouty Ordered to Antarctica, Kennedy Killed

Apropos of the Kennedy assassination aspect of your book, I think the question which is always asked and is always very useful to know by everybody who was alive at the time and old enough to remember, is: “Where were you when John Kennedy was assassinated?” You were, presumably, still active duty in the Pentagon at this time. I would think, given your capacity, that you would have been in a sort of critical position to at least have some window on the security concerns in Dallas, and things like that.

Were you in Dallas that day, or were you in Washington?

Col. Prouty: In November of 1963, I was the Chief of Special Operations, which is supporting CIA clandestine operations for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. A rather unusual meeting. In October, I was walking down the hall and a General said, “Oh, Glad to see you, Prouty. I wanted to talk with you.” He said, “You are being ordered to go to the South Pole with a group of VIP people who are going down there to install a nuclear plant.”

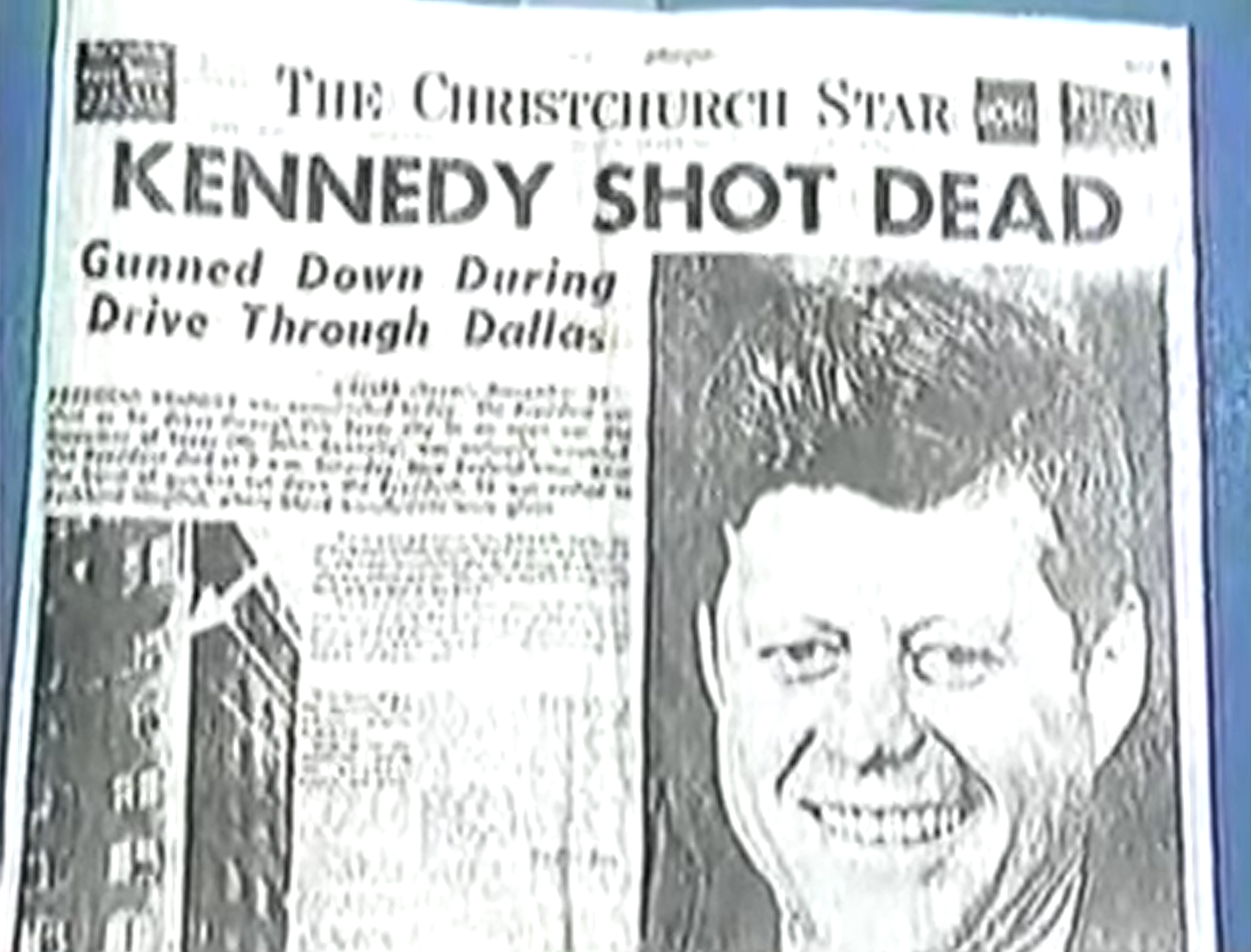

I thought, “Well, nice vacation [laughs], but nuclear? Not by business.” I’d been here nine years in the Pentagon, all on one kind of job. We did have some CIA activity in Antarctica, but not enough to warrant a trip down there. I accepted it in good faith. I saw no problems with it. The next think I know, November 10, I’m on a plane on the way to Honolulu, down to New Zealand, and down to McMurdo Station in Antarctica. We fired up the nuclear plant at McMurdo and then came back to Christchurch, New Zealand.

By that time, I got to know quite well a congressman who was a member of the party. We were sitting down to breakfast. I will never never forget this, because down there it was Saturday morning when the President was killed. All of a sudden the radio in the place said, “Ladies and gentlemen, BBC have announced that President Kennedy has been killed in Dallas.”

Boy, you could have heard a pin drop, clear to Australia. Stunning news. There was nothing we could do. There wasn’t a radio station. We didn’t have radios.

After we finished breakfast, we went out onto the street. A few hours later, I was able to buy a newspaper, the Christchurch Star, which I still have, which was in the JFK movie, by the way. I looked at the paper, at the terrible news, and, of course, had nothing else to balance it against, except some of my own experience. I had worked on a business of presidential protection. You know, the military is trained in presidential protection. I had gone to Mexico City, for example with Eisenhower, when he went there in ’56 or ’57,[14] and so on. I was familiar with it. At times, I had to call certain units to be in certain places to provide extra support to the Secret Service.

Oswald Profile ‘Pre-Packaged’

We were looking at the paper, and up in the corner is a picture of a building, where the man who shot the President was alleged to have hidden, called the Texas School Book Depository building.

As I looked, I saw the windows were open. I turned to the congressman and I said, “Pete, something’s wrong. We don’t allow that. The windows would be sealed if the military were there, if the Secret Service was there. Right beside the picture was a headline that said, three bursts of automatic weapon fire killed the President.[15] Of course, having nothing else to go by, I figured that’s the way he died: three bursts of automatic weapon fire. You know what we’ve heard now: three bullets from an old rifle up on the top of a building. Now, if you go boom, boom, boom, reporters on the top know the difference between an automatic weapon and a [repeating] rifle.

Then, down in the lower corner of the paper, very interestingly, it gave the whole biographical story of this young man, Lee Harvey Oswald.[16] Of course, we read every word of that, and the whole bunch of it on the inside page. It contained a picture of Oswald in a nice business suit. White shirt, necktie. Have you ever seen a picture of Oswald dressed like that?

When I got back to the States, I keep looking through newspapers everywhere to find a picture of Oswald in a business suit, but that’s what had been sent, by radio photo somehow, to the newspapers around the world before the police in Dallas had arraigned him. I took that paper home, and through my resources in the Joint Chiefs of Staff, phone calls, and otherwise checked things out.

The information that appeared in that paper about Oswald’s biography and everything—all of that part of it—had been written and sent before the police in Dallas has arraigned the man. How could a reporter, some 24-year-old boy, have this story all ready to go, if he didn’t know from the police who they had charged with the crime?

Ever since then, I’ve been building up more and more information to see these things that were manufactured, as a cover story, ever since that murder. Of course, the biggest cover story is the Warren Commission Report.

Steinberg: Let me make sure I get this straight. November 23, 1963, in the New Zealand-Australia area is November 22 in the United States.

Col. Prouty: Yes.

Steinberg: In other words, this is really the same day, not the following day.

Col Prouty: No. It’s over the date line. That’s right.

Steinberg: And this newspaper in an obscure area of New Zealand—

Col. Prouty: [interrupting] Well, it’s a big city in South Island, Christchurch.

Steinberg: Ah. so, in other words, this story, the biographical profile [of Oswald] as well as the details of the assassination was about the very first news coverage that reached Australia and New Zealand.

Col. Prouty: All pre-packaged. See? Now, in a few minutes like in this [interview], I can’t go through the whole thing, but to give you some relevancy, here, the President was shot at 12:30 p.m. in Dallas. We heard [about it] at 7:30 a.m. in New Zealand, the “next day.” [17]But that will give you how many hours it was. In my book I go through it very carefully, and it comes out. You just see that somebody had prepared this whole story to make Oswald the patsy, just as he said he was, just like in the movie, where they said he was the patsy. He was created for that job, which tells you really more about the whole crime than most of us have been willing to accept, until we begin to realize the facts of life.

1973: Lyndon Johnson on JFK Assassination

Steinberg: The events of the Kennedy assassination. Obviously, from reading your book and from other things, you don’t believe for a minute that Lee Harvey Oswald was the lone assassin of John Kennedy. You pointed out to me quite a few months ago in an earlier discussion that we had, that shortly before his death, President Lyndon Johnson had made some comments about the Kennedy assassination. Could you tell us about that? Was it an interview, I believe?

Col. Prouty: That’s one of the most interesting things I have read since the assassination, because you know, a lot of people say “Well, of course Lyndon Johnson was implicated, and so on.” That couldn’t possibly be.

But, just before Johnson died in’73—he had had some serious heart trouble, and I’m sure the gentleman knew he didn’t have long to live—he had [a conversation with] an old friend who was a writer, named Leo Janos. Janos wrote for The Atlantic Monthly magazine.[18] Anyone who’s interested should look in the Atlantic Monthly of July 1973, [for Janos’ article].[19] I’ll quote the best I can. Johnson told Janos he always believed there was a conspiracy.[20] Now that’s a pretty big statement for the man who appointed the Warren Commission, but Johnson told Janos that he always believed there was a conspiracy.

Second, Johnson said that although Oswald may have pulled the trigger, he wasn’t the only one, acting alone.

Johnson’s third statement hits like a thunderclap. He said “We have been operating a damn Murder Incorporated” in the government.

‘We Do Run a Murder, Inc.’

Now, through my work, regrettably so, I have to admit that we do run a Murder Incorporated. I know where they were; I know most of them are foreigners; I know how they’re used and have used them; and I know how they do the job. And it’s nothing like Lee Harvey Oswald sitting up at windowsill.

When Johnson said those three things, anybody could wrap up the murder and find out what the problem is right there. Nobody, I’m sure, knew the situation closer than Johnson. Remember, for over 19 years, right here in Washington, D.C., Johnson’s across-the-street neighbor was J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover and Johnson were that [puts two fingers together]. What Hoover knew, Johnson knew, except on betting on horses [laughs]. But other than that, Hoover knew what Johnson knew, and vice versa.

So, there are no surprises when you read that this is what Johnson thought in 1973.

‘People Kill for Money, for Military Contracts’

Steinberg: A kind of evaluative question, which, I guess, asks you to take a great deal of the material that’s extraordinarily well document in your book, and sort of put it in a few brief sentences. Obviously, as you emphasize, the question of who were the actual trigger-men is of relatively secondary importance, as to who were the actual authors and controllers of the operation.

So, do you think it’s fair to say that the motives behind the Kennedy assassination had to do with the sort of monumental policy changes that he was about to effect? Could you give us a sort of characterization of who, in general terms, was responsible for this?

Col. Prouty: Well, that’s a good way to put it. There’s no way, in a brief period [such as this]—I’ve done it as best I can through the book—to explain that when Kennedy became President, one of the first moves he made was giving McNamara orders to hold up on the TFX contract[21]. Everybody kind of forgot about that, but that was a very advanced fighter-plane contract worth $6.5 billion in 1961 money, which is a big contract. That’s only letting the contract. They usually run 10 times that, through what we call “life of type.” That was big money.

They held up the contract, and finally, by a specialized system that McNamara and Arthur Goldberg, the Secretary of Labor allocated the contract to a company that had created an area of subcontracting throughout the country in the political counties where Kennedy needed the vote most. Remember, Kennedy got elected by the skin of his teeth. So, where he had beaten Nixon by only a few votes, we’ll put a little factory there. Where Nixon had beaten him by a little bit, put a bigger factory there. It was a beautiful plan. Walls of the Pentagon were covered with maps [showing the locations of all these factories]. On the 23rd of November, 1962, McNamara allocated that contract [to General Dynamics].

In the halls of the Pentagon you couldn’t hear a civil word. I mean, “Kennedy this,” “that goddamn Kennedy this,” because everybody knew that the contractor that the Eisenhower administration had set up.

Things like that create pressures. Saying he’s not going to put Americans in Vietnam. That war ran to a minimum cost of $220 billion, probably all up, $500 billion. People will kill for money like that. They’ll kill for contracts within that. Ten million men were flown to Saigon by commercial airline. It was worth a billion dollars. They wouldn’t [otherwise] have gone.

‘The Decision is Clean, the Cover Story is Difficult’

When you create that kind of pressure, you create what it takes to murder a president. The decision is very clean, handled by a few people, the gunmen come from outside the United States, nobody knows about it. There’s no Cubans involved, there’s no mafia involved, there no this involved. These people that talk about it: that’s cover story. Cover story is the most difficult thing to run. This one’s been running for 30 years now. Think of the pressures that cover story has been creating over the last 30 years to keep it up front, to have really famous, intelligent newspaper men say there’s no substantive history except that Oswald killed Kennedy, and so on.

It’s a cover story. It’s ridiculous. The American Medical Association trotted these poor old autopsy people out who said “Well now, the bullet went this way and went through Kennedy—came out his neck, of course—went down into [Texas Governor] John Connally, broke his wrist, went right through his head.

A cover story is a terrible thing to create. Murder is simple. Just a little scalpel that you’re doing.

Steinberg: I hate to break off at this point. I wish we had another three hours to continue, because we’ve really just barely scratched the surface, but I want to just say, Colonel Fletcher Prouty, thank you very much for being with us here. Your book is one of the most thought-provoking and critical pieces of historiography that I, for one, have ever read. I think it’s essential reading for anyone trying to get to the bottom of contemporary history.

This is Jeff Steinberg. I want to thank you for being with us today for The LaRouche Connection.

Footnotes

[1] Ludwig Schwerin von Krosigk was Minister of Finance (1932-1945), never Foreign Minister.

[2] Westminster College is in Fulton, Missouri, not Kansas.

[3] Gen. Nathan F. Twining served as Air Force Chief of Staff from June 30, 1953 to June 30, 1957.

[4] JMWAVE, also known as “Miami Station” or “Wave Station,” operated 1961–1968.

[5] Col. Jack L Hawkins.

[6] Charles P. Cabell was a U.S. Air Force General and Deputy Director of the CIA.

[7] Dean Rusk was Secretary of State from Jan. 21, 1961 to Jan. 20, 1969.

[8] Richard M. Bissell, Jr.

[9] National Security Action Memoranda (NSSAM 55), “Relations of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to the President in Cold War Operations,” is dated June 28, 1961.

[10] The U.S. Agency for International Development.

[11] Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Vol. IV, Vietnam, August–December 1963, Edward C. Keefer, editor, U.S. Govt. Printing Office, Washington, 1991. Available on line at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v04.

[12] National Security Action Memorandum Number 263 (NSAM-263) was approved by President Kennedy Oct. 11, 1963. It was revealed to the public in 1971 in the Pentagon Papers. NSAM-263 is available online here: https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/JFKNSF/342/JFKNSF-342-007.

[13] James “Jim” Garrison was the District Attorney of Orleans Parish, Louisiana from 1962 to 1973, best known for his investigations into the assassination of President Kennedy.

[14] Eisenhower visited Mexico three times: Oct. 19, 1953, to dedicate Falcon Dam; Feb. 19–20, 1959, to meet with President Lopez Mateos; and Oct. 24, 1960, again meeting with Lopez Mateos.

[15] The blowup quote from the Christchurch Star reads: “Three bursts of gun fire, apparently from automatic weapons, were heard. Secret Service men immediately unslung their automatic weapons and pistols.”

[16] The introductory blurb to the article reads: “Dallas (Texas), November 22. Police have arrested a man employed at the building where a rifle was found after President Kennedy’s assignation. British United Press reported.”

[17] 12:30 pm, Nov. 22, 1963 in Dallas, is 7:30 pm, Nov. 23, 1963 in Christchurch.

[18] Leo Janus was also a speech-writer for Lyndon Johnson.

[19] The full article is available on line at: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1973/07/the-last-days-of-the-president/376281/

[20] The actual quote from Janos’ article: “During coffee, the talk turned to resident Kennedy, and Johnson expressed his belief that the assassination in Dallas had been part of a conspiracy. ‘I never believed that Oswald acted alone, although I can accept that he pulled the trigger.’ Johnson said that when he had taken office, he found that ‘we had been operating a damned Murder Inc. in the Caribbean.’ A year or so before Kennedy’s death, a CIA-based assassination team had been picked up in Havana. Johnson speculated that Dallas had been a retaliation for this thwarted attempt, although he couldn’t prove it. ‘After the Warren Commission reported in, I asked Ramsey Clark [then Attorney General] to quietly look into this whole thing. Only two weeks later he reported back that he couldn’t find anything new.’”

[21] The Tactical Fighter Experimental. Proposals were received from Boeing, General Dynamics, Lockheed, McDonnell, North American, and Republic.