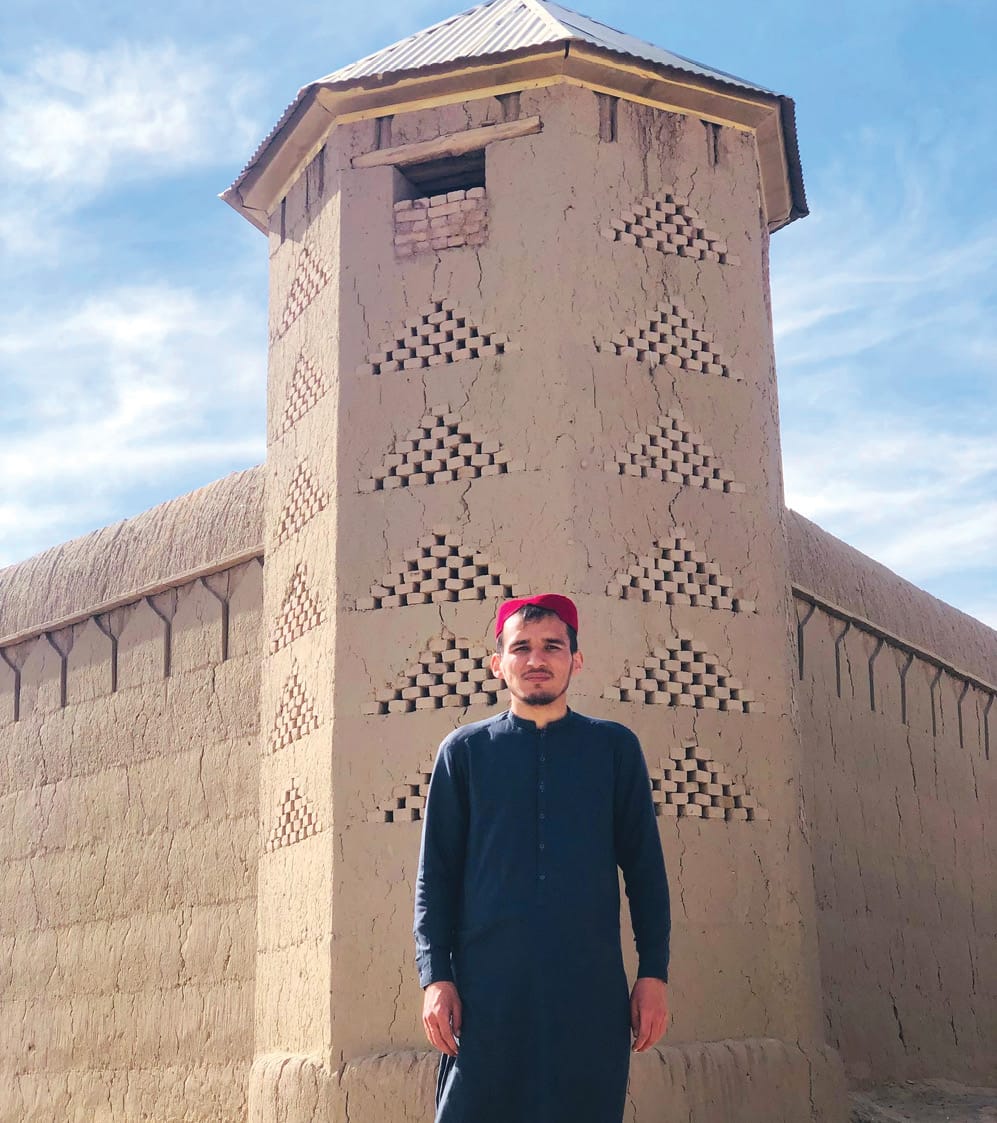

Last November a delegation from the Schiller Institute attended the Ibn Sina Research Group Conference in Kabul, Afghanistan to discuss the country’s future. In January, Jason Ross, one of delegates, interviewed Abdul Wasi Wahdat, co-founder of Light Path Afghanistan, and one of the Afghan participants at the Kabul conference. Wahdat and his organization work to expand educational opportunities across Afghanistan, particularly in rural areas.

Jason Ross: My name is Jason Ross, and I’m interviewing Abdul Wasi Wahdat from Afghanistan. He is a courageous young man, and he’s leading a mission for expanding education in his country. I believe, Wasi, you were just on a trip out to one of the provinces. Why don’t you tell us what you did, so we can learn about what your group does?

Abdul Wasi Wahdat: Sure, let me tell you first of all about what we do, and from where we started in Light Path Afghanistan. Light Path Afghanistan is a non-profit, non-governmental organization that I and one of my friends, Kamran Rayan, founded in 2021, when the political change happened. The amount of stress and pressure among the young people and also children drove us toward this decision that we have to do something meaningful for our community. Looking through my own background, and also Kamran’s, we are coming from places where usually there are no institutions, no platform so that people could thrive. Also, I see the changes that I have experienced through education and how education helped me in how I understand the new world, and also how we can, through education, help our community in different fields.

So, that was the idea: Let’s do something. We have enjoyed this journey, so let’s pave the path for those who cannot do that, or for those who are not aware of what’s going on in the real world. So, they are mostly living in the past, stuck in the past. Some of the people were even thinking that King Zahir Shah was the President of Afghanistan when Ashraf Ghani was the President. So, there are two different worlds. Two or three hours is the entire distance between Kabul, the capital, and those remote areas—Paktika province, and then Logar province, Paktia province and also those remote districts. So, the decision was, let’s do something for them. Let’s help them to realize the new world. And also, let’s tell them that through education you can thrive and you can be as successful as everyone else.

So, there was a decision that we decided to found this non-profit, non-governmental organization. We have named it Light Path, which is, in Pashto, De Rana Lar Afghanistan (د رڼا لار افغانستان).

So, through this, the idea was to serve the underprivileged and also marginalized community, specifically those who live in the very remotest areas of Afghanistan. Multiple other organizations and nonprofits are working in the major cities of Afghanistan. But no one is considering doing something beneficial and meaningful for those underprivileged communities living in the remote areas and rural areas. There are no institutions, there are no schools, no educational centers. So, we wanted to pave the path for those people who live very far away from the capital and the major cities.

This decision drove us to go into those communities. In the first stage, when we started, there was a taboo in our community where they thought that the people of the Pashtun area, in this tribal area, are not very supportive of education. Although Kamran and I both came from that specific area, we wanted to know if that was true or not. So, through this initiative, we went to every major district, talking to the tribal leaders about what they think of education; whether they let their daughters or sons be educated or not. Quite to the contrary of what we had heard, the people were quite appreciative of the idea. They said, “You just bring a system, and we will provide you with (for example) the places and accommodations. How long will you stay here? You bring us the stationery, books, and supplies. You have 100% our complete support.”

That was something we never expected, but it gave us tons of energy. When we came back to Kabul, we talked to our different professors, our other mentors about this journey and idea. Also, my professor was quite appreciative about this journey, and told us, “That’s your responsibility. Now, you have to take a step and go to all those communities.”

So, the first beginning, we started distributing story books for children. We have distributed over 2,000 books to children in many districts, specifically Loya-Paktia provinces, which includes four provinces of Afghanistan, namely Logar, Paktia, Paktika, and Khost. In these four provinces, we have distributed over 2,000 story books. Then, also we have established a library in Paktika province, which has over 1,000 books about multiple subjects. Self-help books for both girls and for boys. On our recent trip we went there to evaluate the work and the impact of that library, especially because I had never been to that library myself. Other volunteers and Kamran went to the library when it was inaugurated. When I went there, I saw the people, and a few elders came in and thanked us for the library and how it has affected their children. At least 10 of the children are coming to that library every day and reading. They are talking with each other, having a debate or something about specific matters.

I thought: this work is something that we have to continue. We have to expand the work in different parts of the country. Also, in the recent trip, as you mentioned, we went to Omna district; it’s a very far district. If you travel for 30 more minutes, you’d be in Pakistan. So, it’s near the border to Pakistan, that is, the Durand Line. There, the people were mostly nomads, going seasonally from one place to another. But right now, they are building their own houses. There are over 15 families living there with 30 children that are eligible to go to school. But there are no institutions for them. So, we have established a school for them; we have built a school there, and we have provided stationery books for all of them. There is a sort of iPad that you can write on, which is an incentive for those children. We have provided all these things, and I’m sure when our documentary is published, you will see that.

That was a trip that gave me tons of energy and lots of new ideas and experiences of how we can improve, enrich, and enlarge this non-profit. A lot of our friends in many other places are finding this quite interesting, and we have been receiving calls and messages through our social media accounts on how we can collaborate and how to further this mission. That is something that gives us energy, and we are going forward to enlarge and expand the work.

Working with the Taliban

Ross: That’s really fantastic. This is an inspiring mission that you have. The way that you’re describing how the library is being used, [how] the schools are being set up, it makes me wonder: What’s the relationship between what you’re setting out to provide with Light Path, and what you would hope that the government would be able to do? Do you see these as complementary, or what’s the relationship there?

Wahdat: We believe that we have a role to play in the fact that we should help our communities. Also, the government is responsible. If you want to be a government, you have responsibilities to provide services to your people. As a part of Light Path, we are not only doing the work, we also are advocating for the authorities of the government to reopen the girls’ schools. Education is something that we need if we want doctors, engineers, linguists, teachers, educators, lawyers, and also professional policemen. For these things, education is the foundation. If you want to build a community that prospers and also be a successful country in the battle of civilization and also in such a complex world, education is the foundation. So, the government should do their part. We are always meeting with the current authorities of different ranks, whether ministers or deputy ministers, and asking them to reverse the decision, and order the girls’ schools to be reopened, and that a system be set up and put together that responds to our current needs, the current needs of Afghanistan. So surely there is some relationship between what we do and what the government has to do.

One of the things that we provide is the education, and the government is responsible for doing that. For me, I would think that the government should do their part. And as a very helping force, we could help them, not on a large scale, but on a level that is within our capacity. For example, if the government could not reach that far because of financial resources, at least if I could get the financing then I could do the work for them in the very far areas of the country. So usually we are working with them and we are sharing ideas.

Also, the legacy media are sharing usually adverse news that the situation is not that good in Afghanistan. I would say, it isn’t as bad as the media shows it. The security has been improved. For example, in the previous government, you could not travel to that area that I went to on this trip. It’s a seven-hour trip, so it’s not easy to do that. That is a connection between me and the government; the government is providing the security to go there.

Also, the people say that the government is against education. OK, I have been talking to their top-level, high officials. They also are appreciative of this initiative. They are saying it’s a good idea. Recently I was talking with one of the deputy ministers, and he said, “How can I help you from my personal budget? How much money do you need, for example, if you set up a library in that specific area?” which he himself suggested. He didn’t tell me, “I’m going to provide you this document, this topic, that you have to get books like this, or all must be religious.” He didn’t say anything like that, he just said, “How can we help you to get the books and set up these libraries?”

There is the connection; there is the idea. So, I think we can do that together, as long as you don’t have a political agenda behind it here, and you’re not supported and have a connection with the intelligence of foreign countries, the government is appreciative of the idea. The people in the government are divided into two categories. One is the old guard, which have their own ideas about education. But the new guard, which is the ministers, deputy ministers and also the lower-ranking people, are quite supportive of the idea. Also, they understand the importance and the value of education in Afghanistan.

This is the idea. I believe we can do that. I believe we can fight for education. I believe we could be the force of change through education. And the government is supportive so far.

The Challenge of Education in Afghanistan

Ross: This is really good at dispelling a lot of images that, as you put it, the legacy media present to the world about Afghanistan. It’s very heartening to hear what the real situation is on the ground, and that it’s so favorable to your work.

Let me ask, how did you come to be involved in this? How did you and Kamran decide to set up a non-profit to promote education?

Wahdat: For myself, I think I have told you this before. My family was involved in promoting education since 2001. My father did a lot of work and established two schools in my village. That was the first time a girls’ school was established in that district of Logar province. So, since then, the idea of education and how we can be empowered—or the community gets empowered—through education was cultivated in our minds through my father’s work. I think it was the seventh semester of our university, so I was talking with Kamran, and that was the time the previous government collapsed. There was a situation of uncertainty, especially for the young people, considering that over 70% of the population of Afghanistan is under 25 years old. So, everyone was desperate. Some wanted to get out; some were in the situation where they didn’t know what to do. There was a brain drain in Afghanistan. A lot of people who got educated, who were professionals in different fields, they wanted to get out of Afghanistan.

This question in my mind was always: If I, with all of this education information and capacity I have, if I leave Afghanistan, then who is going to build this country for us? My nature is that I usually criticize the older generation of Afghanistan; for example, my father and grandfather. Because they have left a Third World country for us; their legacy is not very beautiful for me personally. So, I usually criticize them. The question is, if I criticize the older generation, then what can I leave for the next generation that comes after me?

I was talking through this idea with Kamran all the time. And Kamran was saying, “OK, that’s a good idea. How can we not be like them? How can we do different things?” I said, “Let’s do something the others don’t. Let’s not leave Afghanistan to serve other countries that are already developed countries, that are already rich and at the peak of success.” Afghanistan is truly in need of its young people. So, I told him, “I think if Afghanistan wants to be a progressive, prosperous country, there is only one way: that you educate every single Afghan in Afghanistan.” Through education, we can build this country. We have a lot of natural resources; we are not facing a lack of resources. We have a lot of things. We are a rich country, but still very poor.

You have to acquire the knowledge of how to use these resources. The only way is to learn it. Education is the only way that you can understand all these things. The reason we have decided to put a structure together and do the work, the things I know, the information I have, let’s give it to everybody in this country. A lot of surveys have been made, and research that we have read. One reason for us to act is what sets our organization apart: that what we do is in the very remote areas of Afghanistan. No one goes there, not UNESCO, not UNICEF, no one. So, that’s what makes our initiative unique.

Ross: In going to these remote areas, how do you figure out where to go? How do you choose your locations?

Wahdat: As I mentioned earlier, Kamran and I came from that specific area, so we are familiar with many districts, like Omna. There are other networks available there that are also working in promoting education in this specific area. So, there are other nonprofits which are not registered with the government actually. They are working in that Paktika province. So, they have located that specific area for us, and then we went there for a survey. We realized this is the most underprivileged and marginalized area. They are truly in need of this service.

We usually talk to them on the phone and we also go visit there, and make a connection and relationship between us and the tribal leaders. If they see a potential there that we could help them through education, we could set up a school, we could set up a classroom, a library, in four months there is a specific area. So, if you do the work, it could be quite positive for the community and for the young people.

There is a network which is not very formal, but nevertheless a network. And also, we have the experiences and familiarity that Kamran, myself, and the other volunteers that work with us have with this specific area. We locate the area and then we go for a survey. After we have completed the survey, and we found that that area is truly in need of this service, then we can give them the thing they want.

Education Is Key to Development

Ross: We met in November in Kabul, at the Ibn Sina Research Group Conference that was held there for a few days. In that conference, there was discussion of education, of infrastructure, of health, of culture, of energy, of water, of many subjects. I wonder if you could say more about how you view the mission of developing education in Afghanistan as part of the nation’s overall development?

Wahdat: I think, as I mentioned, education is the foundation for all of them. If you want to work on the industrial sector, you need educated individuals, technicians, who have to go through some certain education. If you want to do work on the energy sector—there is a great need—it’s essential that people be educated. Afghanistan has not had expert people in these areas, technicians. So, unfortunately, all of the time, even in the past 20 years, we were asking foreigners to help us do technical work. So, the foundation of all of these fields is education. There is a great potential for developing education in multiple areas; whether that’s energy, the culture, or also the educational system that could be set up for them.

I think that the type of education system in Afghanistan is not quite responsive to these needs. So, there is a need of that, and that’s why Stay In Afghanistan is doing great work here in bringing new educational ideas that are quite needed. We think it would be very helpful in that area, to serve as a bridge, a connection between Afghanistan and Germany. The potential for education is greater than any other sector. If you need a technician, if you need an expert, you need a doctor, you need an engineer, they have to be educated.

We usually say, everything cannot be moved away or cannot be done by the mullahs, the imams of the mosques. That’s what we are discussing with them every time we meet them: “OK, you have the government right now, but you cannot do the technical work. Let’s give this work to the professional expert people.” Unfortunately, a great number of experts have left Afghanistan in the past two years. I think it’s a great loss to the country. But if they are not willing to come back, what do we do? The question is here.

So, let’s set up the infrastructure, let’s set up the system, and let’s educate new individuals. Let’s give them the potential and also the idea. One issue is that usually the young people who are educated and bright people, are not willing to work with the current authorities, because the current authorities show less respect to these individuals. They have their own agendas. I’m not going to enter into that domain. However, if you want those people to come back, all those experts, if you want these people to help you build our country, give them the opportunity. Give them the platform, and see what they do. If you don’t do that, you cannot understand their true intentions: whether they are able or not; whether they want that or not. So, that’s the thing.

The potential for education is much greater than any other sector, I believe. The development of that should be collaboration between the non-profits and the government should be supportive of this idea.

A Bright Future for Afghanistan

Ross: Let me ask one final thing before heading into how people can learn more about you. Your sentiment that you transformed from disappointment with the older generations, and you channeled that into saying that you wanted to make sure that when you’re an old man—I hope you have a long life—that the next generation would not have reason to be disappointed in you. With the change of government in Afghanistan, with the end of the foreign presence, has this engendered among young people more generally a sense of openness about what the future of the country can be?

Wahdat: The first impression that we got, for me personally, was quite negative. Because the past 20 years we have been told that the Taliban is evil, and they would come to kill and butcher every one of us. Also, the idea of the Taliban about us is quite negative. So, there is a conflict of ideologies between us. So, the first point, we were uncertain, and also afraid of the situation. We were not very hopeful of the country; we thought it was the end of everything. The government will start going backward, and we are not going to develop; especially when the Taliban came in and closed the educational centers, schools, universities for girls, and also the work domain for them. We thought, “OK, we are not going forward; progress stops for us.” There was an old idea that said Afghanistan is not going to build, ever. So, I was very disappointed myself.

But now after two years, after sitting with officials, talking and seeing the progress in the country, and the work they themselves do, is something that gives us a lot of energy. We think, “OK now, let’s do the work. They want to build Afghanistan; we want to build Afghanistan. So, why shouldn’t we join them and work together?”

When you put the positive energy together, usually things get easier, and you can achieve your objective much sooner than you think. Right now, there are major projects ongoing in multiple provinces, which give me personally a lot of energy. I think, “Yeah, Afghanistan is going to be a very developed and prosperous country in the future”: a country that helps other countries; not that sits here and waits for the charity of foreign aid and foreign nations. This is the idea.

I think there is a potential in the idea at the beginning. When the Taliban first came to power, and right now, these are two different things. Many young people that I talk with are also quite optimistic about the future of Afghanistan. Personally, there are domains where we are not supporting their policies; especially in the education area. I usually talk with them, and I confront them. I say, “That is a mistake. I support this and this area in your project. That one is good; this one is better. But the education policy that you have taken is completely against the interests of the country; it’s against the beliefs of the country; it’s against the culture. Even against the belief of Islamic and Sharia law. So, let’s cancel all those policies that are harming Afghanistan in the future, and put in place a policy that helps everyone.”

Usually one of the things that’s quite common among them, is when we ask, “If your wife, your sister, your mother got sick, which would you prefer? Do you want to take her to a male doctor or a female doctor?” The 100% answer is “female.” “I don’t want my female family members to go to a male doctor.” So, OK, if you don’t open the university, how can you have female doctors? So, open the education infrastructure in Afghanistan.

I think the idea has been changed compared to two years ago. I think there’s a positive change. I think we could help each other, and we could build Afghanistan all together. I think another civil war, and another foreign troop presence, is not going to help anyone. Let’s all come together; let’s unite together. Let’s build the country from the ground up. How do you do that? You educate everyone about this potential that exists in the country.

Ross: Very inspiring to hear about how this dialogue process is having an effect, transforming people’s views by having a direct discussion.

So, how can our viewers learn more about your work? Where can people turn to learn more about, or to support your efforts through Light Path?

Wahdat: We have established social media accounts, on Twitter—Light Path Afghanistan (@LightPathafg)—and also on Facebook and LinkedIn. Currently we are working on a very comprehensive website also. But there is not a specific infrastructure yet. As of now what we have done—I should mention this—what we have done is all self-financed. For example, we were talking about this yesterday. Over $5,000 have been spent on our work so far. It’s all self-financed from our volunteers and also personally from Kamran and myself.

So, there is no infrastructure for fundraising that we have done so far. The registration is roughly completed with the Ministry of Finance of Afghanistan. When it is done, surely we will be establishing some others, because we cannot do all these things alone by ourselves. One of the greatest challenges, as of now, is quite the contrary of what people think. Perhaps people think the Taliban are putting barriers against our work, which is absolutely a fabrication. The Taliban is supporting us. The only challenge we are facing now is financial resources. We have very little, and we are in great need of financial resources to expand the work. Not one school, not one library, but to create another 100 libraries, 100 schools, or 100 classes to help thousands. So, the challenge currently is the finances, and we are working toward that.

So, the social media is available for everyone if you want to see our work and the credibility of Light Path Afghanistan. Shortly, we will be working on a comprehensive website, and we will publish the link for the website on all our social media. Light Path Afghanistan on X or Twitter; Facebook; LinkedIn. You can reach out and see what we have done so far. All of the work has been published there. Usually it’s in Pashto language; also in Dari. But you could use Google Translate, or reach out to us to help you.

Ross: Great! Thank you so much for sharing your work, your vision, your optimism, your energy. I think what you’re achieving is a real inspiration, and I hope that our viewers will be interested in learning more and being able to help you in your efforts.

Wahdat: Thank you.

Ross: Thank you very much for your time. Is there anything else you would like our viewers to know?

Wahdat: One other thing I usually talk about with our foreigners who love to follow us through social media, is that what the media shows you and what is true about Afghanistan are two quite different worlds. Afghanistan is a beautiful country. Yes, we have been a war-affected country for over 40 years. But currently the situation is much, much safer. Yes, there are adversities, I don’t say Afghanistan is a perfect country, but it is much better than the media shows. So, don’t believe it. And to those watching, the education system, what we are working toward, is something noble and your help would be very appreciated. Make sure that if you have any questions, any concerns, any new ideas that you think would help us through this, your expertise and your consultation would be very helpful in our work. We would really appreciate that. And thank you for watching this interview.