This article is adapted and published with the author’s permission from his blog, where it was posted May 19, with additional illustrations and quotations. Karel Vereycken is an infrastructure journalist with the Schiller Institute in France.

The current onslaught on Palestinians in Gaza is stirring up growing resentment amongst those around the world who still have a conscience. Even worse than Israel’s war crimes are the hypocritical responses from the so-called leaders of the democratic world, who pretend to cry for Israeli victims but turn a blind eye to the Palestinians. Even the strongest defenders of humanity turn toward feelings of despair and hopelessness, while solutions to this conflict often seem more elusive now than ever before.

However, a brief look at the political debate in the United States during the middle of the 20th Century shows that solutions have in fact been available, and were at one point even widely discussed at the highest levels of government. During the period of the early 1950’s through the late 1960’s, the U.S., for its own reasons, did promote ambitious proposals for the economic development of the Southwest Asian region as a whole, envisioned as a sort of economic-development-for-peace policy.

Hence, after the Six-Day War of 1967, the U.S. proposed the use of peaceful nuclear power for large-scale desalination and abundant energy creation. If both the Israelis and the Palestinians had access to abundant fresh water and energy for agriculture, industry, and living, they thought, this could provide the optimum conditions for a peaceful coexistence between all people of the region.

This article shows that leading circles in the U.S. had at one point worked to solve the underlying causes of this seemingly intractable conflict. This is a role which it absolutely should step into again, adopting a win-win orientation which could pave the way to a solution to this ongoing conflict today.

The ‘Johnston Plan’ for Water Sharing

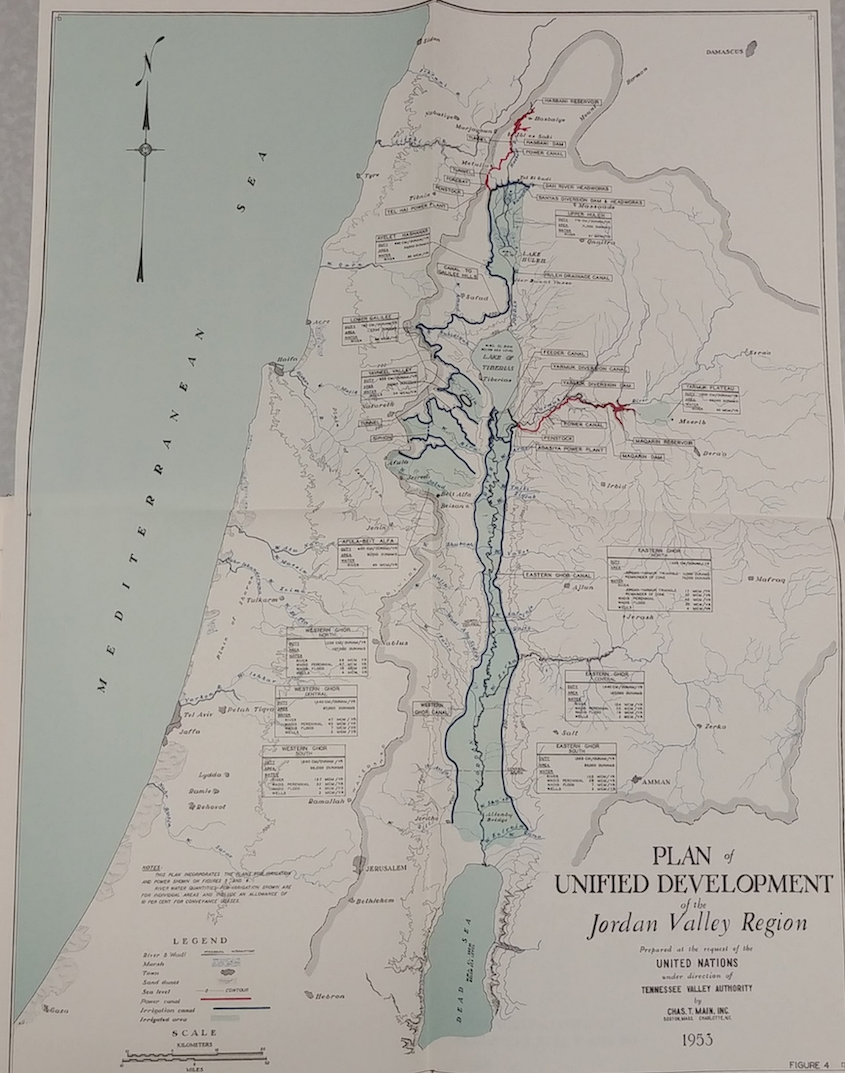

In the early 1950’s, at the request of the United Nations Refugee Works Administration (UNRWA), experts of the US Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), had designed an equitable water-sharing program for the entire Jordan River Basin involving Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria.

Just as had the original TVA, the program would have used the construction of irrigation canals and dams to expand irrigated farmland and upshift the economy and living standards with energy from hydro-power.

In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower, pressured by his Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, sent Eric Johnston as his envoy to convince all nations involved to adopt the scheme known as the “Johnston Plan.” Dulles wanted to fight communism without wars. His view was that to avoid countries willing to escape colonial exploitation joining the Communist or “neutralist bloc,” the United States should offer development programs and keep them on “the right side of history.”

Unfortunately, on March 28, 1956 Eisenhower approved the secret OMEGA Memorandum, whose aim was to effect a reorientation of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s policies toward cooperation with the West, while diminishing what were seen as his harmful attempts to influence other Middle East countries. Under Nasser, Egypt was the first, after Nepal, to recognize Communist China. Nasser did this on May 16, 1956, without informing his allies. Pertaining to measures directed at Egypt, the Memorandum had provisions that included a delay by the United States and Britain in concluding negotiations to finance the Aswan Dam on the Nile River in Egypt.

As a result, John Foster Dulles, in cahoots with the British and the U.S. southern cotton lobby, went ahead with suspending U.S. financing—which would have been 90% of the cost—of the Aswan Dam, Nasser needed the dam to irrigate farmland.

On Thursday, July 19, 1956, Secretary Dulles asked the Egyptian Ambassador in Washington, H.E. Ahmed Hussein, to come to his State Department office. When Hussein arrived, Dulles handed him a letter announcing the withdrawal of the United States offer to grant $56 million toward financing the construction of the High Dam at Aswan.

This decision unleashed a chain of events leading to the famous “Suez Crisis,” which, fortunately, President Eisenhower brought to a halt, once he realized it could end up in a nuclear conflict.

As a result, the most precious aspect of the “Johnston Plan” for the Middle East—that of mutual trust-building around the perspective of a shared, common future, was ruined after the Suez affair. Instead of working together, those nations which should have been partners of one single global plan to share and expand the waters of the Jordan Basin, went each its own way, alone.

Israel went ahead with its own National Water Carrier, tapping fresh water from the Sea of Galilee into a water-conveyance system, bringing water from the northern border with Lebanon to the Negev Desert in the south.

Jordan, with U.S. financing, built the Eastern Ghor water-conveyance system, now called “King Abdullah Canal,” to provide water for Jordan’s agriculture and capital. Syria constructed a dam on the Yarmuk River, one of the tributaries of the Jordan River. This situation, with each struggling over limited water resources, led to war within just a few years.

The Shock of the Six Days War

In June 1967, following border clashes over water resources and what appeared as a military mobilization of its Arab neighbors, Israel staged a sudden, preemptive war against Egypt, Jordan and Syria.

On June 5th, it destroyed more than 90 percent of Egypt's air force on the tarmac. A similar air assault incapacitated the Syrian air force. Within three days the Israelis had achieved an overwhelming victory on the ground.

On June 7 Israeli forces drove Jordanian forces out of East Jerusalem and most of the West Bank. The UN Security Council called for a cease-fire that was immediately accepted by Israel and Jordan, while Egypt accepted the following day. Syria held out, however, and continued to shell villages in northern Israel.

On June 9 Israel launched an assault on the fortified Golan Heights, capturing it from Syrian forces after a day of heavy fighting. Syria accepted the cease-fire on June 10. Israel’s decisive victory included the capture of the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank, Old City of Jerusalem, and Golan Heights; the status of these territories subsequently became a major point of contention in the Arab-Israeli conflict.

The Arab countries’ losses in the conflict were disastrous. Egypt’s casualties numbered more than 11,000, with 6,000 for Jordan and 1,000 for Syria, compared with 700 for Israel. The conflict created hundreds of thousands of refugees and brought more than one million Palestinians in the occupied territories under Israeli rule. Months after the war, in November 1967, the United Nations passed UN Resolution 242, which called for Israel’s withdrawal from the territories it had captured in the war in exchange for lasting peace.

For most western elites, including Jewish elites, the Six-Day War came both as a shock and a reminder that the two main causes of war had been left unsolved: refugees (that of Palestinians pushed out and Jews arriving) and water sharing.

Nuclear Desalination, the Talk of the Day

Immediately after the Six-Day War, however, the perspective of a massive investment in water and energy to solve the refugee and water issue in the Middle East, became the talk of the day. By these dramatic events, thanks to the men and women willing to respond to them, the science, the technology, and many of the plans that had already been elaborated between 1945 and 1967 to use nuclear power for peaceful aims came back onto the table.

Key in this was leading U.S. nuclear physicist Alvin Weinberg, who was the administrator of Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) during and after the Manhattan Project. Weinberg was appointed in 1960 to the President's Science Advisory Committee in the Eisenhower Administration and later served on it in the Kennedy Administration.

Weinberg inspired and organized his networks to propose projects for the peaceful use of civilian nuclear power. Weinberg's career was brutally terminated when he was fired by President Richard Nixon in 1973 for pleading, just as Edward Teller did before his death, in favor of thorium fueled molten salt reactors (which don’t produce plutonium for nuclear bombs).