When Rear Adm. Thomas Buchanan, the director of plans and policy at U.S. Strategic Command, told a Nov. 20 CSIS Project on Nuclear Issues conference that if there had to be a nuclear exchange, “then we want to do it in terms that are most acceptable to the United States,” he wasn’t just spouting off one man’s opinion about victory in a nuclear war. The madness he expressed is institutional. The very same day, an article appeared in Foreign Affairs, co-authored by Madelyn Creedon, a former deputy director of the National Nuclear Security Administration, and Franklin Miller, who has been in and out of the Defense Department on nuclear weapons matters for about three decades, in which they demand that incoming President Donald Trump should just go with the madness once he takes office. Creedon and Miller call on Trump to skip the time-consuming effort to review U.S. strategic and nuclear policies, something every new administration does, and simply get to work. Afterall, the Biden administration, they say, has already gotten it right on the Russia-China-North Korea threat. Therefore, Trump and his team should just go with it. “A quick senior-level review within the administration should suffice,” they say at the end. “This not only will preserve a well-functioning policy but also will avoid a waste of senior-level focus and get the much-needed updated plans in place sooner.”

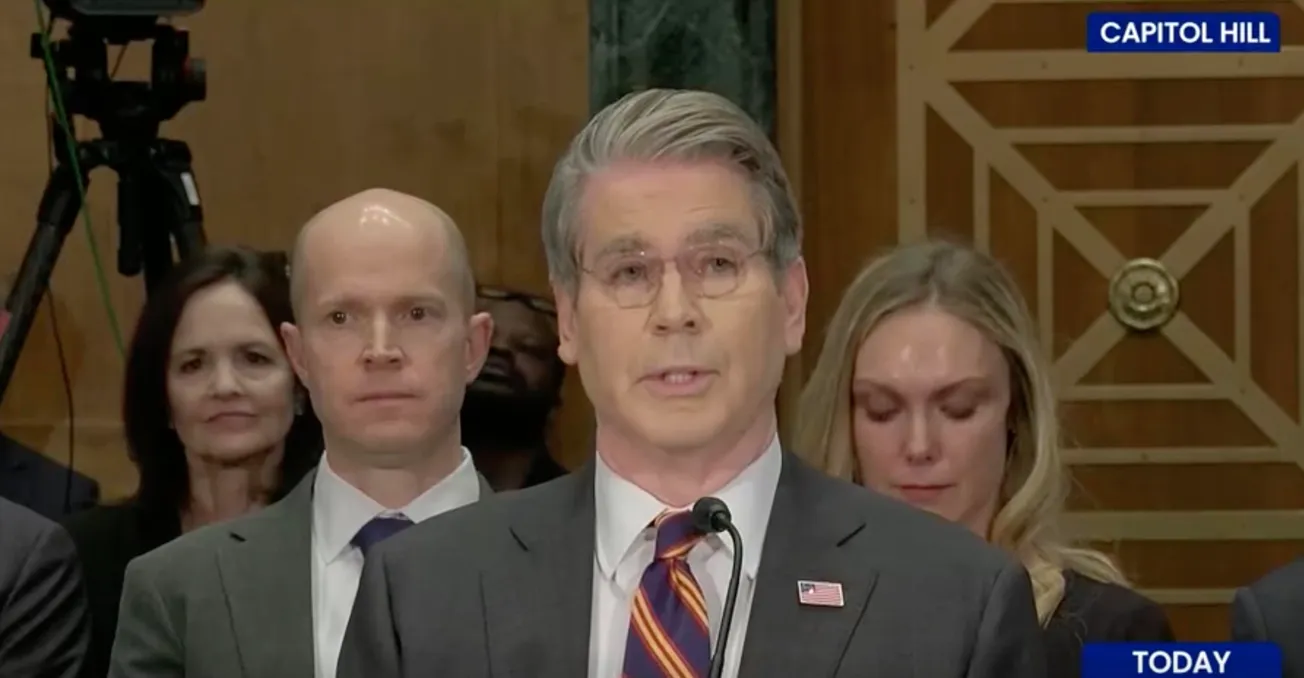

In the CSIS conference, Richard Johnson, deputy assistant secretary of defense for nuclear and countering weapons of mass destruction policy, paraphrased the administration’s policy documents as saying that as the security environment evolves, changes in U.S. strategy and force posture may be required to sustain the ability to achieve deterrence, assurance, and employment objectives for both Russia and for the People’s Republic of China. “So, to that point, we have been engaged in an interagency U.S. government process for some time, looking at the changing strategic environment and its implications for current and future U.S. nuclear policy,” he said.

Just a few days before the CSIS conference, the Biden Administration had released an unclassified summary of the Nuclear Employment Guidance. “That guidance builds on the findings in our 2022 National Defense Strategy and the Nuclear Posture Review,” Johnson added. “And, importantly, it directly informs the development of nuclear employment options for consideration by the president in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States and its allies and partners. It recognizes that the United States faces multiple peer—excuse me—multiple nuclear competitors, with each adversary presenting unique deterrence challenges for the United States to confront, and stressing strategic stability in a diverse number of ways.” The policy documents Johnson referred to set the narrative of Russia as an existential threat to the U.S. and China as the “pacing challenge” to U.S. military superiority.

Grant Schneider, the vice deputy director for strategic stability in the Joint Staff J-5 Strategy, Plans, and Policy, noted in his remarks that the policy isn’t just about deterring the alleged bad behavior of Russia and China. “It’s also about the potential to provide options to respond in the event of actual conflict, should the decision be made to do so by civilian leadership,” he said. In other words, nuclear war fighting is an inherent part of the Biden Administration’s strategic policy.