Scott Spencer is the Chief Project Advisor for InterContinental Railway, which features the Bering Strait Tunnel. He has been a rail industry consultant for a number of railway projects, including developing the start-up and operating plans for the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority’s (SEPTA’s) Center City Regional Rail Tunnel, and the Philadelphia Airport Line; the Cairo Metro; and the Taiwan High Speed Rail project. Richard Freeman interviewed Mr. Spencer for EIR Sept.10, 2025. The following is an edited transcript. Subheads have been added.

EIR: On August 15, U.S. President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin held a summit at U.S. Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, in Anchorage, Alaska, which went for about three hours. The day before, you gave an interview to TASS, in which you said, “With regard to the upcoming summit, I personally believe the InterContinental Railway is one of many things that I believe President Trump and President Putin can agree on. It would be mutually beneficial for their countries.” Why do you think this is so important?

Scott Spencer: Because when there have been so many differences between the countries, particularly with the military conflict between Russia and Ukraine right now, and the implications with other countries, NATO and the United States, the question comes up, how do we move on? How do we rebuild relationships?

Throughout history, there have been any number of military conflicts where relationships had to be rebuilt, trust had to be rebuilt, reparations [paid], rebuilding of the countries, and so forth. All those are things that are in motion between these countries. That’s why I suggested that the InterContinental Railway could be an incentive for both countries to consider, because for every year it’s not running, there’s a significant opportunity cost, opportunity lost in strengthening our economic ties, our political ties, our transportation ties. That was why I mentioned it.

And the other reason is that, despite the differences between our countries during these years of the conflicts between Ukraine and Russia, [Russia has] successfully maintained the relationship with the United States and other countries, Japan and countries in Europe, with the International Space Station. To me, that is a shining example of—despite the adversity—how we can find a mutually beneficial way to cooperate.

EIR: You’ve called the InterContinental Railway the Panama Canal of the 21st Century. Why?

Spencer: Because the Panama Canal is part of the success of global commerce. Various countries depend on being interlocked politically and economically, which it’s made possible. The Panama Canal has brought the world closer together. It really was a major breakthrough, along with the Suez Canal, in generating efficient success of global commerce. And so, the InterContinental Railway would achieve the same thing by becoming a major conduit for global commerce through the Bering Strait Tunnel. And I likened it to the Panama Canal because of its equivalent capacity of the canal. We’re expecting when it [the Bering Strait Tunnel] opens to have, right away, 100 million gross ton-miles carried per year, because there’s that much commerce already—and we’ll get a slice of it. That’s not even including some of the resource access that will be economically efficient in eastern Siberia and Russia, or throughout Alaska and northwestern Canada.

Because it’s a double-track railroad, it ultimately has a capacity, four times that, of 400 million gross ton-miles a year, and that’s about the equivalent of the Panama Canal. That’s why I said it’d be like the Panama Canal of the 21st Century.

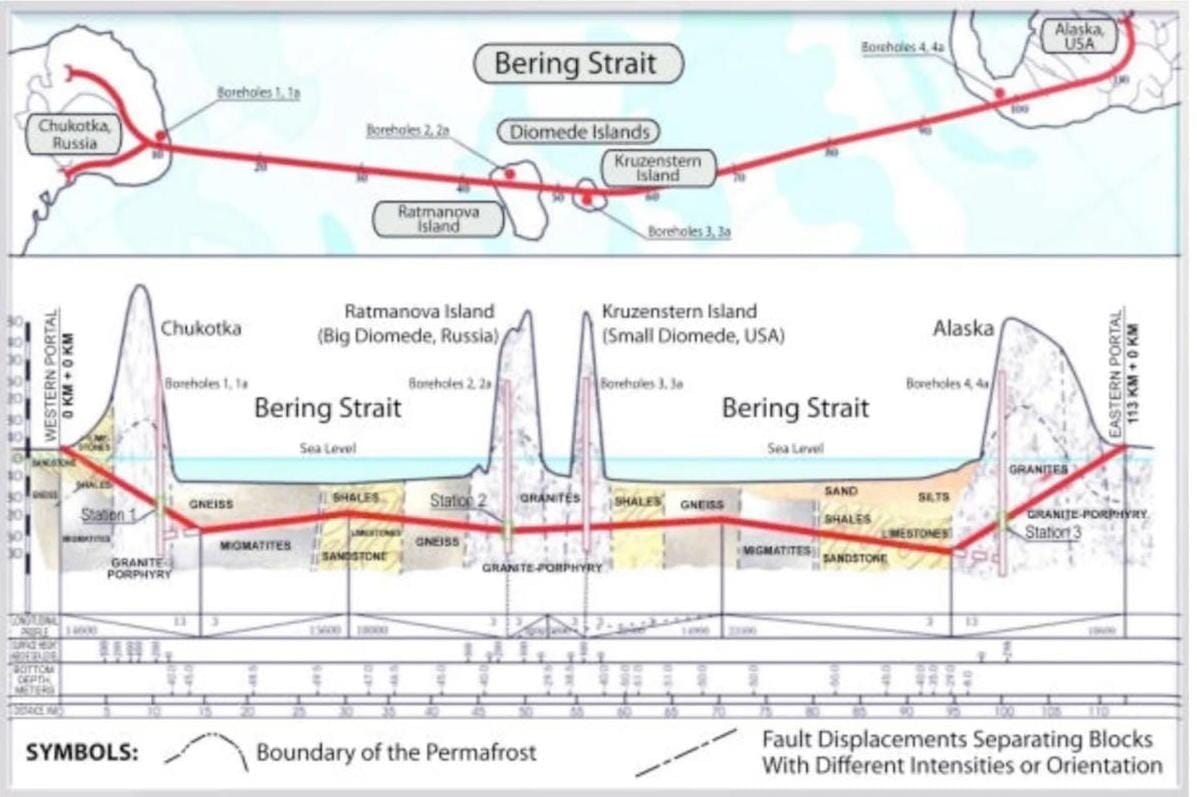

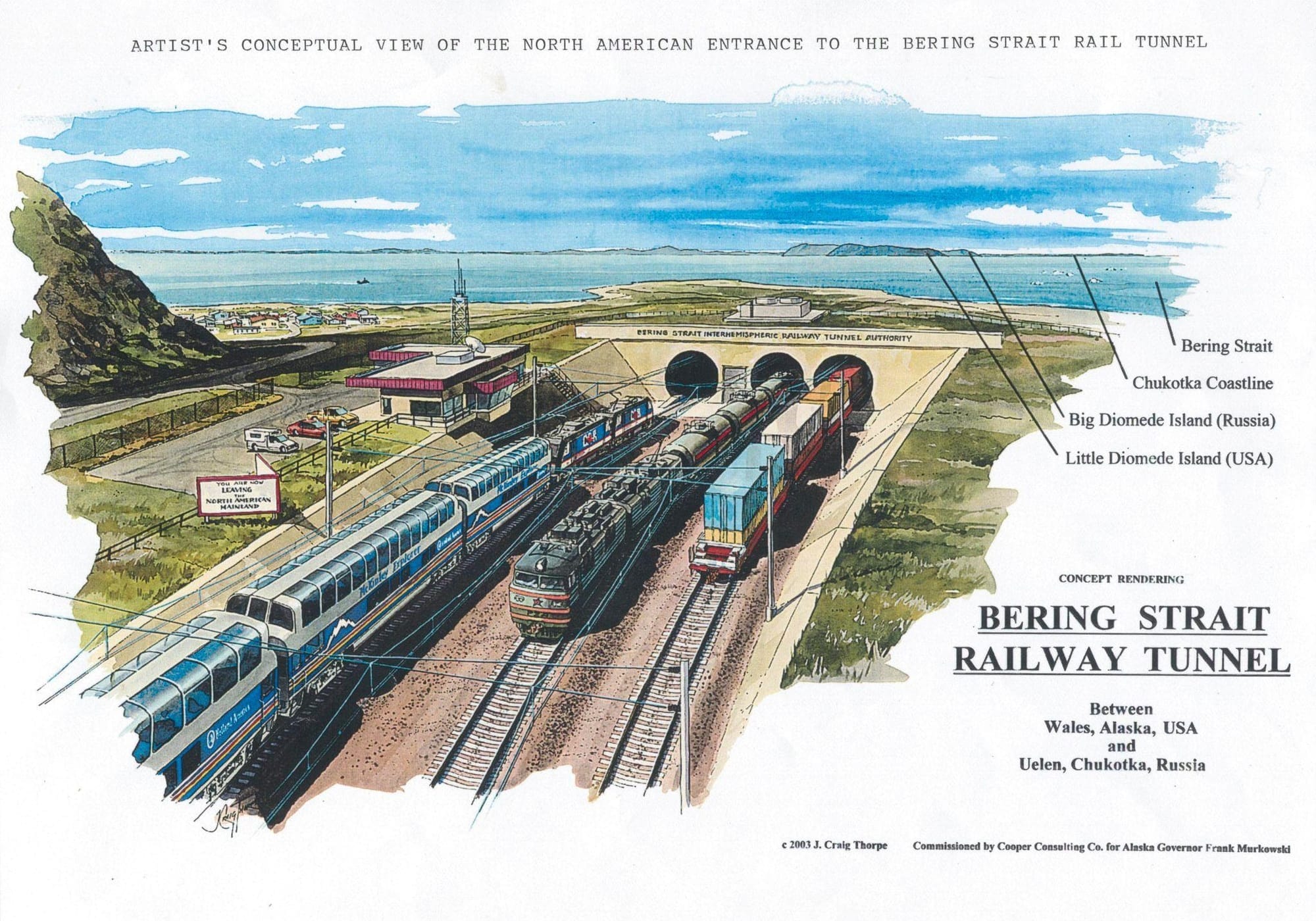

EIR: The critical Bering Strait Tunnel, which will connect the Western and Eastern Hemispheres, will be between 60 and 70 miles long. To give people a sense of this, imagine looking out at the Bering Strait from the westernmost part of Alaska, from the tip of the Cape of Prince of Wales. In the Bering Strait, there are two little islands, one is called Little Diomede Island, which belongs to and is nearest to the United States; the other island, nearby, is the Big Diomede, which belongs to Russia.

Spencer: The islands are two-and-a-half miles apart. I’ve been to Little Diomede, and I can say, when I was doing the dishes there, I looked out the window and could see Big Diomede. I actually did that when I was staying there. You know, when we went to Little Diomede, there are no hotels, there’s no restaurants. We had to bring our own food, MREs [meals ready to eat] and so forth, and cook in the town schools. Less than 100 people live there year-round. But anyway, washing dishes, I always enjoyed doing that, looking out the kitchen window of the school, right across the Bering Strait. Actually, I was looking into tomorrow, because they were 24 hours ahead of us—in the time zone across the two-and-a-half miles.

EIR: People may not know, but the international dateline intersects and runs through the Bering Strait. From Big Diomede Island, one proceeds to the Russian shore, and it’s called Cape Dezhnev. It’s also called Uelen. Tell us what’s involved in building the tunnel from Cape Prince of Wales in America to Uelen in Russia.

Tunnel Design, Construction

Spencer: I’m not an engineer, so part of what I’m going to say is definitely qualified from what I’ve learned from those, such as one of our founders of the project, George Koumal, who has since passed away, but he was a mining and tunnel engineer. And then, his colleague, Joe Henri of Alaska—they both worked very closely with our colleague, Victor Razbegin in Russia.

Looking at a lot of resources about the feasibility of doing this, because when you stand there at the Bering Strait, as I did at Wales, looking out towards Little Diomede, it just looks like it would be insurmountable. But actually, when you get to know the area, despite how formidable it is, first of all, it’s a tough environment that you can only construct [in] a few months of the year, but it’s still below the Arctic Circle.

And we would envision that the rail lines from the United States to Canada, and then across Alaska, would approach the Bering Strait, as well as from Russia, on the Russian side, so that it would be able to mobilize a lot of the materials to this very, very remote part of the world. Along with, perhaps, some cargo ships supporting some of the materials.

But, even though it’s longer than the English Channel rail tunnel between France and England, it’s actually less difficult to build than the Channel rail tunnel—because the Channel rail tunnel had all types of [underlying] materials that were soft, and silt and things of that nature, that were not very stable to support tunneling.

The Bering Strait, believe it or not, the deepest part is very shallow; it’s only about 150 feet in its deepest part. Most of it is solid granite material. That is very good for tunnel-boring machines and tunnel stability. That’s good. And then we’re blessed that in the length of this 70-mile, 100-plus-kilometer-long tunnel, there’s two islands virtually in the middle of the project. (See Figure 1.) And that’s really important for air ventilation, and also construction staging. We’re really blessed that those two islands are right there, so that’ll be important.

The other factors, which we have said to the Native American population in Alaska, the ultimate design of the tunnel and its approaches, and where the actual portal in Alaska will be, will be decided upon with the Native American territory there, so that we do not disturb their subsistence living, and the wildlife that they depend on, and the natural source of living, such as salmon berries. All that’ll be part of what’s negotiated. Perhaps the length of the tunnel will be a little longer to avoid impacting those natural areas that are important to their way of life. And they appreciate that, that we came and listened to them about some of their concerns.

There’s a number of considerations here to do such a massive project, but the bottom line: It’s definitely feasible, in a construction capability.

EIR: In that tunnel, you would have one tube or lane going in one direction, another lane going in the other direction, as I understand it, and the third lane would be for both work that would be done on either of the two lanes, and for other types of project requirements.

Spencer: Right; it’s really, essentially, three tunnels. The two rail tunnels, one for each track, and in between them is a servicing tunnel, which supports maintenance access to each track. We have overhead electrification systems, signals, track work, and the servicing tunnel will also double as an evacuation tunnel for any of the crews that are down there, or any passenger trains that would run through the tunnel. And also, it would support the ventilation flow through the tunnel, balancing the ventilation flows.

Then, the other thing that’s going to be unique about this railroad tunnel, we’re going to have border security on the U.S. tunnel, in terms of customs and fencing and so forth, as would Russia have on the Russian side as well. The customs will be negotiated in the treaty—how that will be worked out, what’s most efficient.

On the Russian side, around Uelen, that part of eastern Siberia, we’re hopeful, because there’s still, believe it or not, generations of relatives on both sides of the Bering Strait that have had very little easy contact with each other in subsequent generations, so, we hope that the ability to visit, and also the type of commerce that would occur locally between those communities, would be restored.

Rail Lines to the Tunnel

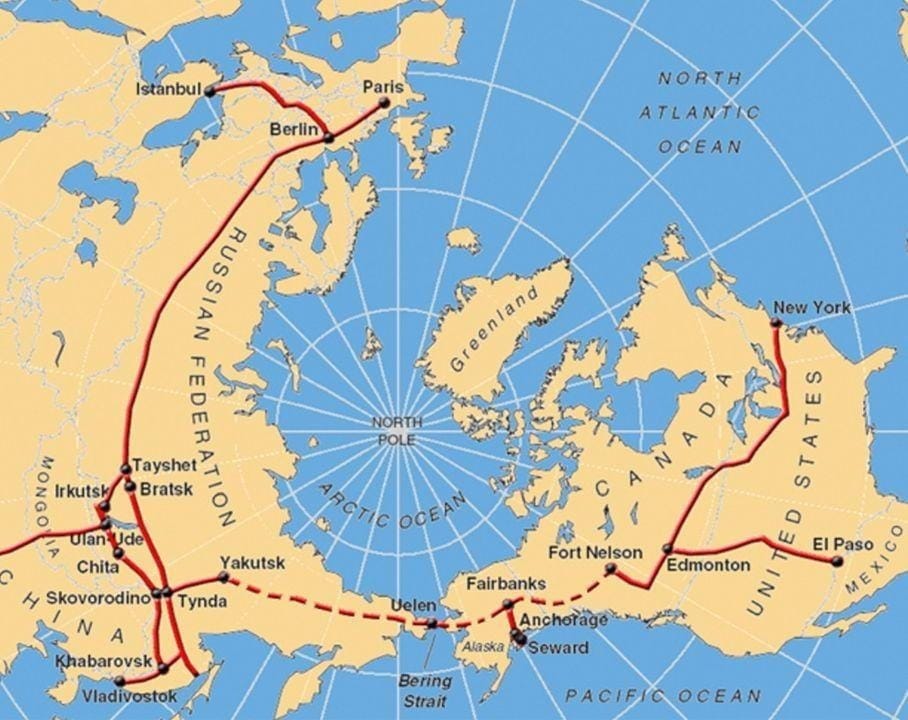

EIR: Another important, equally challenging matter: There are no existing Russian, nor American-Canadian railroad tracks that reach the Bering Strait. This will require the building of approximately 5,500 miles (8,850 kilometers) of new railway lines. On the Russian side, there exists the Amur Yakutsk Mainline railway, which extends to the city of Yakutsk, and ends there.

From the United States-Canada side, the U.S.- Canada railway grid extends up to the municipality of Fort Nelson, Canada, which is the end of the line. The InterContinental Railway report, “Connecting North, Russia, and Asia by Rail,” states that from the Russian city of Yakutsk to Uelen on the tip of Russia facing the Bering Strait is 2,392 miles, and that from the municipality of Fort Nelson, Canada to Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska facing the Bering Strait is 3,030 miles. So, that’s a combined total of 5,422 miles.

The InterContinental Railway, in its infrastructure program, asserts that there should be built 5,422 miles of double-tracked railway, so that the Russian and the United States-Canadian rail networks can connect to the Bering Strait.

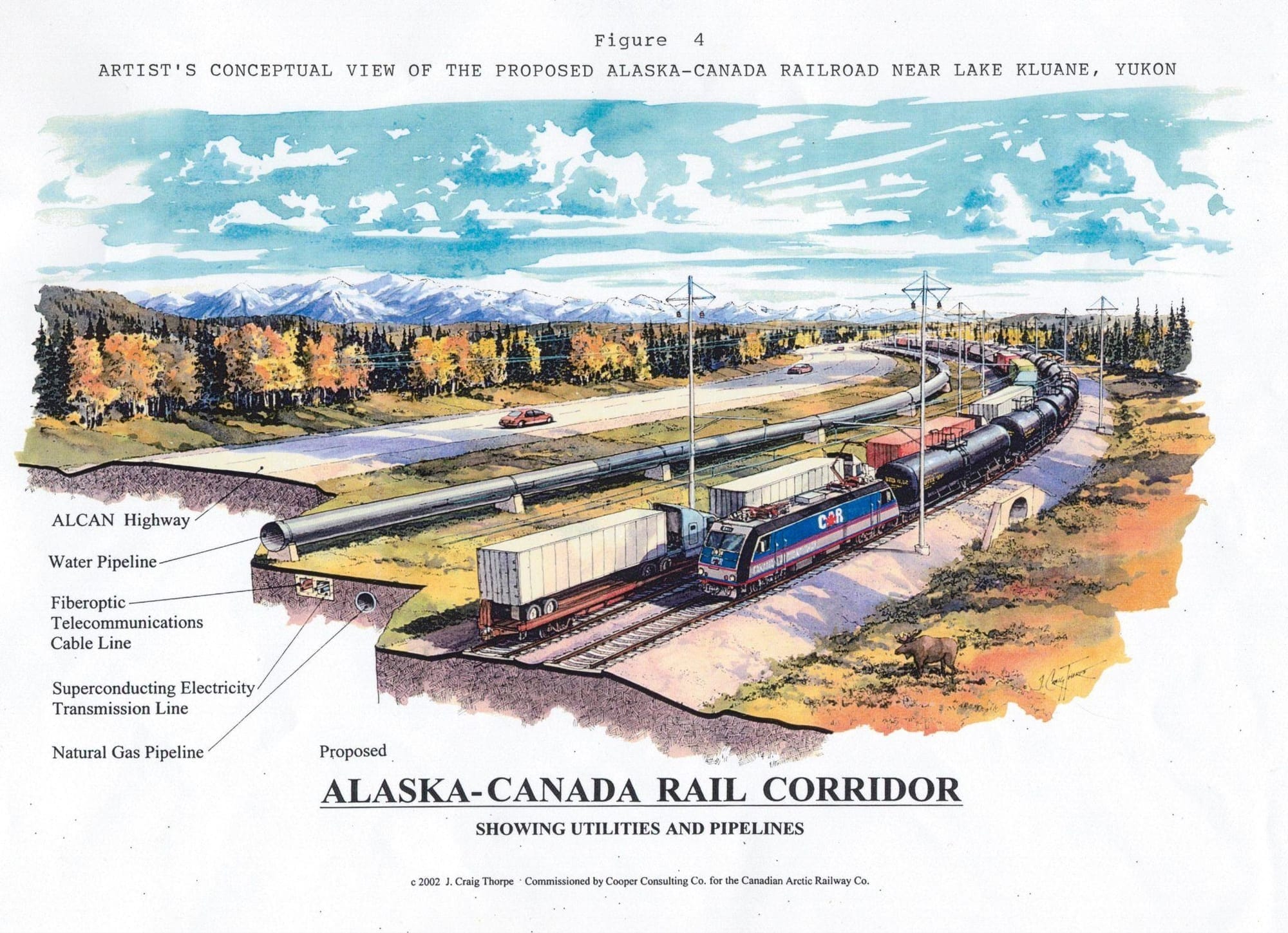

Spencer: Right, it’s more challenging than just that, because it’s also mountainous railroads, particularly on the North American side, with tunneling and bridges there. And then, on the Russian side, they showed us the technology, but it’s still a substantial engineering and construction effort to build railroad tracks on tundra and maintain stability. You know, they’ve done it. They are certainly the world leaders in building railroad tracks across tundra, but it doesn’t make the job easy, that’s for sure.

And then the other factor, engineering-wise, is the gauge-change. The Russian gauge is slightly wider at about 5 feet width and we’d have to develop use of gauge-changing technology, or dual gauge, because the Chinese system is standard gauge [4 feet 8.5 inches width], like the rest of the United States and Canada and Mexico. And global commerce would flow easily if the same rail cars could flow between [Russia], China, and North America.

EIR: What would happen when a train passes from the United States to Russia?

Spencer: We probably would change locomotives, but the rail cars themselves can have what we call gauge-changing technology in the wheel sets, just slide in or out, depending on the gauge. It’s designed to do that. There are several places in Europe, particularly between points of Europe and Spain, where they cross the border and do a gauge changing to the wider gauge in Spain. It’s a well-established technology.

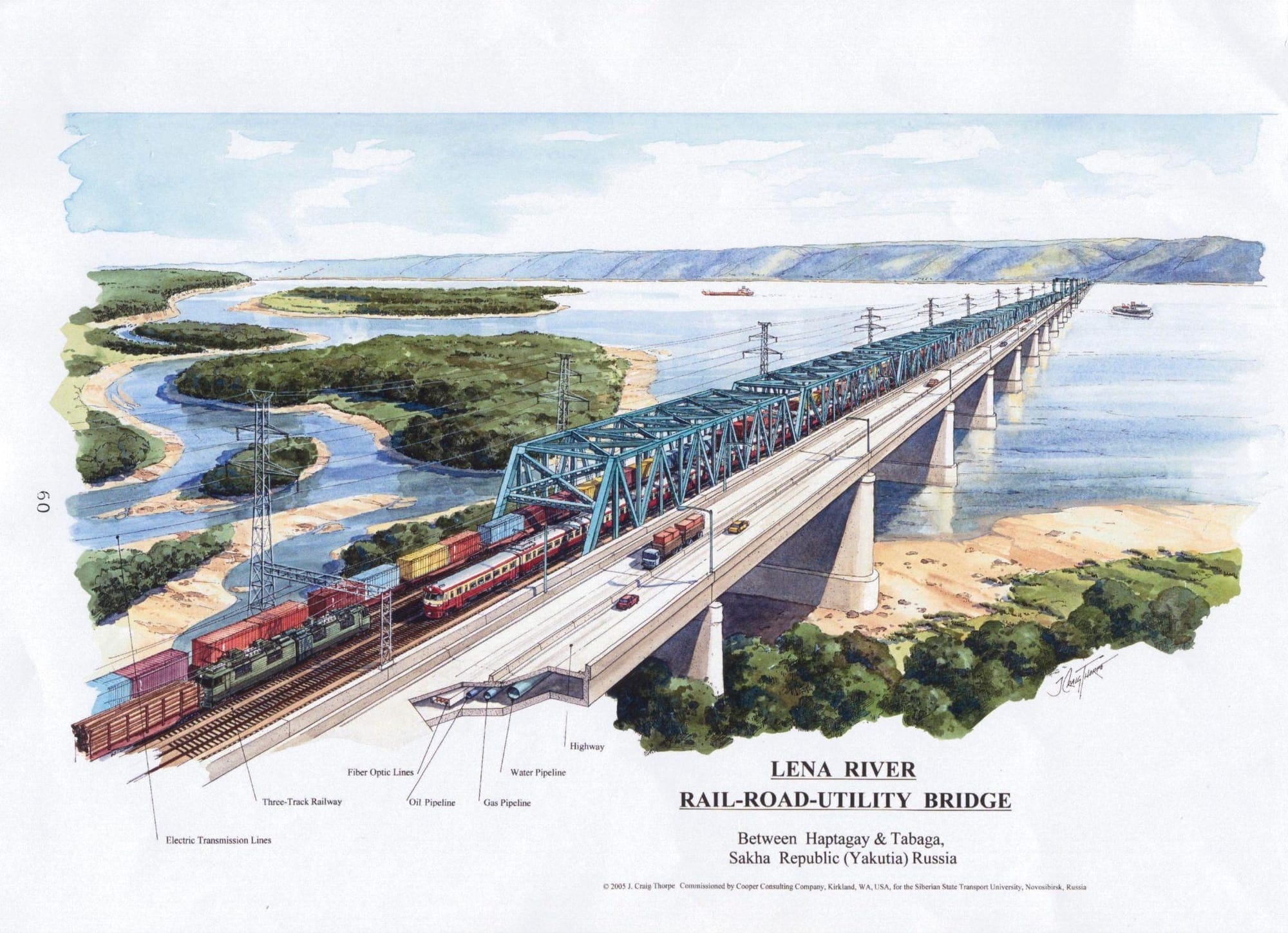

For the most part, we’re envisioning, certainly the tunnel is going to be double tracked. And as much as feasibly possible, the connections on both sides of the tunnel will be double-tracked because of the volumes. I mean, at 100 million gross-tons a year, you’re having 40 or 50 freight trains a day, that’s not easy to do with a single track. So, we expect the route to be entirely double-tracked, plus to be electrified, because electrification is an efficient way to run the locomotives. There are a lot of sources of electrical power through hydroelectric power, tidal power generation.

Along the route, we can power this with zero emissions and minimal impact on the environment. And electrification will also be important to support communities that would be created along the route.

As well as along the route, the right-of-way would be used for water, transporting water to these locations. It’s a multi-purpose right-of-way in that respect.

EIR: That’s excellent. We may have differences on this one: We also think nuclear power would be very efficient for working on this rail line.

Spencer: Well, how would you transmit that power? And that’s where the electrification transmission lines and so forth along the right-of-way would provide access, whatever the source of power is.

EIR: Could you just say what the difference is between single and double track?

Spencer: Single track is a situation where trains operate in both directions on the same track. But in order to pass, you have to build a passing siding, every 10 to 15 miles, generally, so the trains can pass, and you have to build the passing siding to the length of your longest train. Some trains are up to two miles long, so the passing siding would have to be two miles.

Double track is exactly that. It’s two tracks. We don’t have to worry about where the trains meet. There’s a lot of additional capacity, operating flexibility, because the trains can pass wherever they happen to be. And it’s also good for flexibility. If ever there’s a situation where a train breaks down or becomes disabled, you can easily get around it, whereas with single tracking, you’ve got problems until the train situation is fixed.

Vision of ‘Remarkable Connectivity’

EIR: Now I want to mention a document I sent to you. In the time frame before the Trump-Putin Summit and your TASS interview, Helga Zepp-LaRouche, who is the head of the Schiller Institute, wrote an open letter to the U.S. President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin. She said something very similar to what you said. I wanted to read you a section. She said:

When you are meeting in Alaska on August 15, the fate of humanity lies in your hands. Against all the attempts by the opponents of peace, you can not only bring the war in Ukraine to an end, and with it, eliminate the sword of Damocles of the nuclear extinction of the human species at least over this conflict. But you can also reintroduce diplomacy into the relation of the two most powerful nuclear nations on the planet.

But there is something even more elevated you can do by not only fighting off the threats facing mankind, but giving the whole world a beautiful vision for the future. You could agree to build a rail corridor across the Bering Strait, and with that, the rail and tunnel project, unite the systems of Eurasia with those of the Americas. This project would open up the vast untapped resources of Siberia, as well as the U.S. Arctic resources of oil, gas, precious metals.

She added, “In the not-so-distant future, one could then travel by high-speed railroad around the world, from the most southern tips of Argentina and Chile, in Ushuaia and Puerto Williams, all the way through the Americas, across Eurasia, then with a tunnel under the Strait of Gibraltar, travel all the way through the African continent to the Cape of Good Hope.”

Is that a vision that you share?

Spencer: Absolutely, with some qualifications. One, as a railroader, we would never call such a network of connectivity high-speed rail, because high-speed rail is generally speeds well over 160 miles an hour, 250 kilometers per hour, and with mountain railroading and all that, and curvatures and tunnels, that’s not really anything that’s feasible. The best that we could get on the Intercontinental Railway is some stretches of long, straight track, particularly in Russia and Siberia and so forth—maybe 110 miles an hour would be the top speed. So, we’re not anywhere near the world-class high speed that we think about. So, I don’t see that being economically or technically feasible for the route.

But, to the point, yes, not just freight, but passengers would have all types of remarkable connectivity, cruise-ship-type of experience on board the trains. And, what I also would say is, this network of passenger trains, you know, connectivity worldwide, would be part of what makes the InterContinental Railway successful in terms of peace, progress, and prosperity.

EIR: “Peace, Progress, and Prosperity,” that’s actually on the emblem of the InterContinental Railway.

Spencer: Right, because the logo we developed, with simply a different flag for each country, and the language is the same. It speaks to looking at the world in a different way. We show the entire globe from the northern pole, polar view. (See Figure 2). Most people don’t look at the world that way, but this InterContinental railway’s going to help us look at the world in a very different way. And it also will bring, as the logo says, three very important things: Peace, Progress and Prosperity to all who participate with the InterContinental Railway.

One other comment I was going to make about that network that was described and envisioned. We very much believe, in terms of opportunities for future peace, that a leg of the InterContinental Railway will reach down through the Korean Peninsula, uniting North and South Korea as well. And also, there’s a leg that will also be able to go on to Japan eventually.

EIR: And to the city of Harbin, China as well?

Spencer: Well, yes, that’s the main anchor of the InterContinental Railway after the 5,500 miles, is Harbin, China. It’s a central point for global commerce and connectivity to where all the containers are coming. But, you know, these are all great opportunities that can be achieved with the InterContinental Railway.

Corridors of Development and Opportunity

EIR: Mr. LaRouche, who founded the Executive Intelligence Review, proposed that if you look at the United States’ first Transcontinental Railway, which was started in January 1863, it’s really a rail corridor; it’s a development corridor. And other rail corridors around the world are like that. For 50 miles on either side of the railway, you start to develop small towns, cities, agricultural fields, factories, and manufacturing. And actually, it’s a city-building, and nation-building vector in the right sense of the term, it’s a vector for development. What do you think about that?

Spencer: Absolutely. All those are opportunities that, again, can be discussed and negotiated in a mutually beneficial way for each country’s respective interests.

I would say, speaking for the United States, that in Alaska, they recognize that this is not so much just a corridor of development, but a corridor of opportunity; one that they want to pursue in a responsible way; one that is in harmony with the Native American traditions and the use of the lands. So, yes, I think all that will happen, but you also have to keep in mind, Richard, that this project is so consequential, it determines how countries are working together and trading together for the next 100 to 200 years, at least, when you look at the useful life of these structures, and especially the Bering Strait Tunnel. I think we don’t know as far as what will be created and succeed with this project. But I do know there’s two questions about this project: Who’s going to have the vision and leadership to get it moving? And, once it’s built, the second question’s going to be “why didn’t we do this sooner?”

Look at all the benefits we have of this thing. Could you imagine if we had done this years ago?

EIR: And one follow-on for that, because you raised this with me, you had said the cost might be $100 billion. I think it might be closer to $200 billion. People say, “Oh, that’s such a big amount of money,” as if it was going to be spent for one year only. But you’re talking about a 100-to-150-year use prospect. The initial seemingly great capital cost turns into something that’s very small. It produces tax revenues and other benefits that are far greater than its first cost.

Spencer: Right. You’re asking a very interesting question, because when I have spoken to people about the InterContinental Railway project—and we went on a listening tour a few years ago across Alaska—people are very excited about the project. And then, invariably, the question comes up, what’s it going to cost?

When I tell them it’s well over $100 billion—we obviously have to do further analysis to get a firm engineering, and constructable amount, but we know it’s that much—that seems staggering to people. But I try to keep it in perspective here. First, there’s already an example of very successful U.S.-Russian cooperation on an infrastructure investment that is flying over our heads every 90 minutes, the International Space Station.

It cost over $100 billion when you look at the materials that were provided by the European Space Agency, the Roscosmos, Russian Space Agency, Canada Space Agency, Japan, and the United States. And the shuttle flights to build it were over $100 billion. And then, we’re spending anywhere from $3 to $6 billion every year for the last 25 years just to continue the operating costs and maintaining it. So, it’s been a substantial investment in infrastructure that is temporary, that’s going to be deorbited and taken out of service, at the end of this decade. It’s barely had a 30-year service life.

Now, our project, it’s certainly equivalent in cost, but it’s going to benefit so many people in all these countries for at least 100 to 200 years—and when you divide that cost, even at $200 billion U.S. dollars, for 100 years, that comes down to $2 billion a year.

And yet, the InterContinental Railway is supporting global commerce that is many, many multiple times above that annual project cost. And then, the other thing you can’t quantify is the strength of peace, progress, and prosperity that are made possible by the countries who work together and share in this great endeavor and this great project.

But there’s one other sad reminder, that, I believe, the cost of not doing this project is much greater. We just don’t see how we’re paying for it. But we’re paying for it in very inefficient, you know, global commerce shipping across the seas. To sustain future economic, commerce growth, there’s going to be substantial demand, both in Asia, and in North America for more ports, and more port expansion. Where do we do this in our cities? Where do we do this with pristine coastlines? Even if you could find the land to do it, it’s going to cost a fortune. Much, much higher cost than building an InterContinental Railway. That I can tell you, for sure.

EIR: And the combined port of Los Angeles and Long Beach, California, America’s largest port, has been overcrowded.

Spencer: The InterContinental Railway would be so much more efficient in time and energy usage, and a much smaller footprint on the land than building more of these ports.

That’s where I see a lot of advantages. And when you look at global commerce, this is even better than the Panama Canal, because in order to ship through the Panama Canal, at the origin point [of the goods], you’ve got to spend a day to several days, building up and loading the ship with all the containers.

And then when you get to the destination port, you’ve got to spend a day or several days unloading the containers to trucks and rail.

We eliminate all that time. It just comes out of China, slap it on a flat car [on the train], double-stack it, and we go straight through to destinations throughout North America without tying up ports or times loading and unloading ships. But there’s one other cost I want to just keep in perspective, that really shows that the InterContinental Railway’s $100 billion-plus cost is a bargain. And that is, I really believe it’ll help our nations be stronger and more peaceful, working together with stronger economic ties.

Just look at the cost of the war between Ukraine and Russia; the cost of that war, not even counting the tragic loss of lives on both sides. And the economic loss is there. Just the cost of conducting the war is far higher than the cost of having built the InterContinental Railway. I mean, the United States, in the past year, wrote a check for $61 billion in weapons and materials for Ukraine, just in one transaction alone.

So, that’s a sad fact, when we look at what’s realistic here in terms of costs.

Moscow 2018 Conference

EIR: On September 27, 2018, you and an InterContinental Railway team arrived in Moscow. You attended a roundtable, about the InterContinental Railway at the parliamentary level in the Russian Federation.

Spencer: Yes, the Russian state Duma. It was a rare invitation for Americans to participate, but it was fantastic.

EIR: I know that there you were joined by Dr. Victor Razbegin. For people who don’t know who he is, he is a leader of the Council of the Study of Productive Forces in Russia (SOPS), and works with the Ministry of Transport as well. You also met with Russian Tunneling Association experts, and other important organizations. Tell us about this meeting.

Spencer: It was a fascinating experience, obviously, for someone like me who has never been to Russia before, to be warmly welcomed at all different levels, not just with government officials, but with citizens themselves. They were all very interested in the United States and how we could work together for the common good of each of our nations, and a great deal of respect for the greatness of our nations, and to be sure, there were discussions with officials that I met.

Because [the meeting] had come shortly after Russia had claimed the Crimean Peninsula, and [there were] the sanctions even then.

I just said that I’m a private citizen. By the way, I never made that trip to Russia without first briefing the U.S. State Department. I went to Washington and briefed State Department officials at the Russia desk, and I also debriefed them when I came back from Russia, so I didn’t go in there just blindly, and I was very transparent with our Russian host that I had talked to the State Department before, and I will afterwards. I think there was a great deal of interest to find out, despite the differences then over Ukraine, how we might be able to build past these differences with this project.

That was pretty common along the way. The other thing was, really, in such a different part of the world, and certainly going to Yakutsk, that is the coldest city on Earth. There’s a lot of differences there, culturally and so forth, and the language and all that, but I really did feel at home. I saw a great deal of respect for America, I saw an opportunity to share a great deal of respect for their achievements there and their expertise, particularly there in eastern Siberia.

And, there was an interesting meeting I had with railroad officials in Yakutia [the Russian Republic of Sakha] there at the end of the line outside of Yakutsk, and they were very animated about their plans, about how this rail line would be built towards the Bering Strait, but initially to the Magadan Peninsula for cost reasons, resource access, and so forth.

I’m listening to their plans and their vision for running a railroad efficiently in these harsh conditions, and I realized, wait a minute! This is really remarkable. Yes, I have to depend on a translator, but there’s such a commonality in our commitment as railroaders to run a train, race against time, do it safely, do it efficiently and reliably in these challenging conditions. I said, “this is just like being at home.” It was really remarkable, the shared experiences that we were going through.

They really did honor us. They had a number of locomotives there, and they wanted to give us a short ride through the yard and mainline complex. They made a point to honor us by pulling out one of the locomotives that were built by General Electric in Erie, Pennsylvania. I got on board the locomotive. They pointed out, this was an American locomotive, and sure enough, inside the locomotive cab was the plate, “Built by General Electric in Erie, Pennsylvania.” So, that was touching, that they arranged that for us.

Golden Spike for 250th Anniversary

EIR: That’s great. What can be done to advance the realization of the InterContinental Railroad and the Bering Strait Railroad? You’ve been working on this for three decades. What can we do now? What could people do in America? What could people do in Russia? What could people do elsewhere? This is an idea most advanced in terms of developing the world, changing Russia-U.S. relations, bringing about a different era. Further, what are you doing?

Spencer: I’ve been very consistent on this question for the last couple of years. I was very consistent when Russian television wanted to interview me shortly after the war between Ukraine and Russia broke out, and in my recent interview with TASS, that we have to find a peaceful solution to this military conflict between Russia and Ukraine. It’s just heartbreaking to see the senseless loss of lives on both sides.

I know as a civilization we’re greater than that, and there’s also a clear and present risk for every day that conflict continues, for it to go sideways. I would hope, as I suggested in my interview with TASS, that this project could be a catalyst of what comes next, once we are able to establish peace between Ukraine and Russia, because there’s a lot of pain. There’s a lot of rebuilding that needs to be done; there’s a lot of trust that has to be rebuilt.

And what better way than to get to work on something that’s mutually beneficial, not only for the United States and Russia, but for the world? What comes next after that? We want to see, as we were working on before this war broke out, organizing an InterContinental Railway Advisory Group, primarily of various universities that have different expertise.

We’ve identified universities in Russia that have some great railroad engineering expertise, as well as in the United States and Canada. We’ve identified universities that have great expertise on resource and exploration technologies, for achieving access responsibly to environmental resources, mineral resources, and then, universities in Europe that we’ve approached that are great on putting together treaties between countries, because ultimately, getting it out of the evaluation and talking stage is going to require, as we’ve said on the InterContinentalRailway.com website, it’s going to require a treaty: the InterContinental Railway treaty between the United States, Canada, Russia, and China.

That sets the foundation to all interested parties that these countries have a mutually beneficial interest to see this project succeed. That’ll be important. And then, what I’ve proposed is that each of the participating countries provide seed funding for an InterContinental Railway Development Commission, as much as $75 million to start, so that we could pay consortiums about $15 million each to develop what they believe is the way to design, engineer, and construct the InterContinental Railway.

This is a project that will be a signature project for all involved. I think one of the factors in selecting the team, in addition to engineering and construction capability, is, how much private money can you bring to the table? How much in low-interest government loans might you consider? Those are some of the processes, a bidding process for an international consortium to build a project.

We’ve already proposed getting started next year with the first phase of the project. It’s largely engineered from Fort Nelson in Canada, where a [line of the Canadian National] Railroad is, to just outside of Fairbanks where the Alaska Railroad is. We’re proposing that we’re going to have a great birthday here in America next year, the 250th birthday. And it would be a great project of national significance to build the first phase of the InterContinental Railway to connect Alaska to the lower 48 states. That would be a really remarkable change in the economics of doing business and living in Alaska, and it would be a key first phase, because we’d also want to continue west, at least initially, to Nome, where there’s a port.

We’ve already spoken to elected officials in Alaska and mayors about how this first phase can be done. President Trump, during his first administration, approved the cross-border permit between the United States and Canada, which is what you need to construct a road or a rail line across the border. You have to have a crossing permit. A border crossing permit has already been approved by President Trump.

We’re hopeful that, even though the engineering and the financing is not ready to go yet, that we could have a ceremonial first spike for the InterContinental Railway next Summer with our nation’s great birthday. The first phase to get Alaska connected to the lower 48. That would be a nice next step that, I think, is very politically doable, until our relationship with Russia catches up.

‘A Monument of Peace’

EIR: We’ve discussed this: Any one of the ongoing wars, obviously, the NATO-Ukraine war with Russia, the Israel war inside Gaza, or the situation with people pushing Taiwan for independence, which could provoke certain things with China, and so forth, any one of these could turn into a nuclear war. Some forces may be crazy enough to do it by intent. It’s very possible it could happen by accident. Suddenly a series of events happens very quickly. And once you get into anything like that, after one nuclear missile is launched, each side would probably respond with nuclear launch-on-warning, and various policies which are in place. Therefore, we’re facing destruction of mankind, of civilization.

The InterContinental Railway is talking about building and uniting versus a continuation of policies of wars and geopolitical games, and pitting one nation against another, rather than seeing the common purpose of mankind.

Spencer: I think so. I mean, I see the InterContinental Railway physically being such a remarkable engineering project, with the Bering Strait Tunnel being the centerpiece that, really, it can be a monument to the peace that can be achieved between two nations that have been in conflict with each other for too many years, and it’s not necessary.

In addition to being a monument of peace, I think it can be a great insurance policy for peace, because of the strength of global commerce that it will create between all nations that are reached by a rail service on the network.

And I also believe, because it’s mutually beneficial, that there’s an opportunity to be a smarter civilization, a smarter society, to say, if we’re going to achieve the vision of the InterContinental Railway, as we say, in terms of peace, progress, and prosperity.

I think we have to start having a conversation as others have, but we need to have it on a more official, global scale, so that world leaders will actively work to find a way to eliminate nuclear weapons. Because I’ve not heard it discussed much, but, there’s been a number of close calls since nuclear weapons have been around that we came so close. And one of them was absolutely terrifying when I found out about it, how close we came to a nuclear exchange with Russia during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Most people don’t know how a Russian submarine commander overrode a launch command.

We can’t rely on that type of human intervention if people start inserting artificial intelligence into the command-and-control of nuclear weapons, which could possibly happen. It could be a country like Pakistan. We don’t know. But I do know that, in my view, AI, the existence of AI, is not compatible with the existence of nuclear weapons if we want the existence of civilization to be preserved.

We have to recognize that, and we have to eliminate nuclear weapons. We just cannot take the risk of even one mistake. There’s no such [thing as] a small nuclear mistake with even just one nuclear weapon, right?

So, the InterContinental Railway people would say, “Well, what does that have to do with nuclear weapons, negotiations, or policies?” But the fact is, everybody should have a say in doing that. And I also use this as an example. You know, as countries go, they strengthen themselves and position themselves, with their military, to be able to fight a war, if necessary, 24 hours a day, right? But we have no such diplomacy posture to negotiate 24 hours a day to prevent a war.

We should treat military conflicts, or the risk of a military conflict, the same way we treat fires. Do we sit around and [say] are the conditions acceptable to put out the fire, or who’s coming from where, or I don’t like the way you look to come put out the fire, or I don’t like what you said to me before? Or, I want to blame you because you started the fire. No, we don’t do that. We rush together to put out the fire, then you might want to investigate what caused it, whatever. But when you have a war, or the threat of a war, in a civilization that has nuclear weapons available, we should treat it like a fire and put it out, and we should treat it the way we would fight a war, which means negotiate 24 hours a day, what I’ve proposed as crisis-resolution teams.

But, no, the InterContinental Railway cannot ignore the geopolitical issues, the geopolitical risks. Because, as I said, I want it to be a monument to peace. But if you’re going to deliver that result, you’ve got to be very frank about the issues you’re facing.

A Lifelong Railroader

EIR: How did you get involved in this?

Spencer: I’ve been a railroader all my life. I’ve loved trains since I was in a stroller a couple years old. My aunts used to babysit me and watch trains in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, so I guess it just got into my blood.

But you never know how God leads you in life when you sort of stay still and pray about what you do next, and in this particular case, in 1991, I came across an article in May of ’91 about the InterContinental Railway and the tunnel project, that was written by George Koumal. And I reached out to him in Tucson, Arizona at the time. I was in Wilmington, Delaware.

We forged a friendship that lasted decades, until his passing in 2022. Because I was so close to Washington, I was the go-to person for everyone in presenting and discussing the project in Capitol Hill, and going to the State Department. That’s how I got involved, and I’ve stayed with it every year since. I can’t believe it’s been over 30 years, but the project’s bigger than just 30 years.

EIR: We’re happy for that; encouraged by it.

Spencer: I’m inspired by my friends who aren’t with us anymore, the founders, George Koumal and Joe Henri, I miss them.

EIR: Your closing thoughts?

Spencer: I would suggest to all those who hear this, that they consider reaching out to their elected officials and their contacts, learn a little bit more about the InterContinental Railway on our website, InterContinentalRailway.com. You can reach out to us, because we’re always going to need more people involved in the project as we get this issue with Ukraine and Russia resolved peacefully, and move on to a greater stage for our nation’s future, for the world’s future.

I would ask people to consider learning more about the project, and look forward to this coming down the tracks.