by Nancy and Edward Spannaus

This article was first published in EIR, Vol. 9, No. 18, May 11, 1982.

EIR has decided to reprint this article on the true history of the Monroe Doctrine in light of the President Donald Trump Administration’s recently released 2025 National Security Strategy, which claims to be the “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine. Similarly, the Trump Administration has claimed that the Monroe Doctrine justifies its ongoing aggression against Venezuela. While some readers may think these claims are consistent, the Monroe Doctrine is often confused and misattributed to the later Roosevelt Corollary, which defiled the Doctrine’s original intent. As readers will see below, it would be much more proper to call Trump’s new 2025 National Security Strategy “the Trump Corollary to the Roosevelt Corollary” rather than to the Monroe Doctrine.

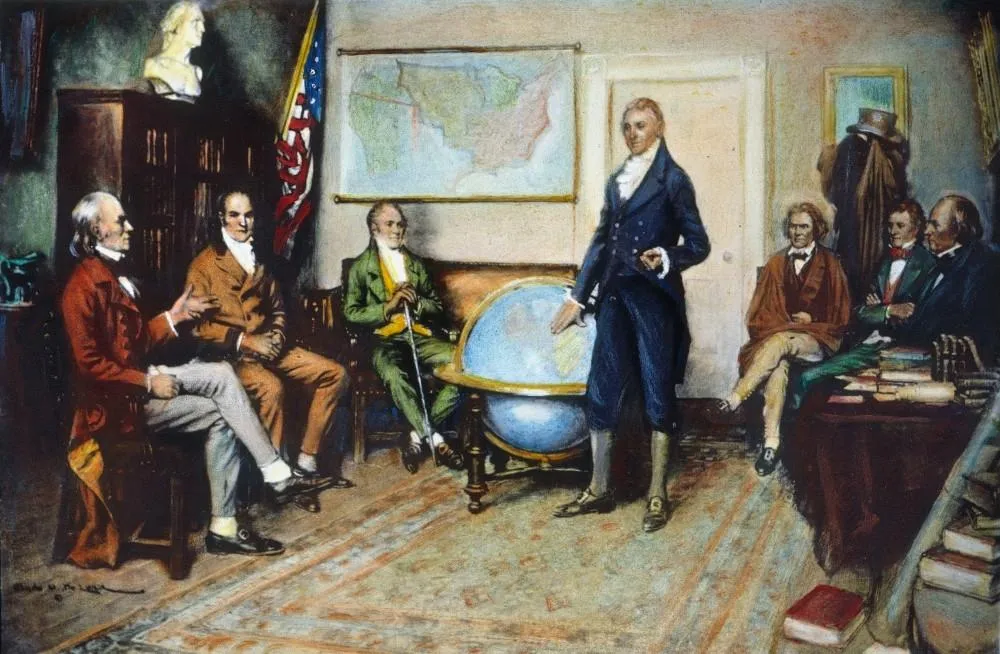

With the declaration of the Monroe Doctrine on Dec. 2, 1823, the United States pledged itself as the unique and sole defender of the republican independence of the nation-states of the Western Hemisphere, against the oligarchical adventures and intrigues of the European nations of the Holy Alliance. This fact surprises most Americans, who have been told that President James Monroe’s declaration was the beginning of a new Anglo-American alliance for imperialist domination of the emerging nations of Latin America. But a review of American history shows that the primary target against which the Monroe Doctrine was established, and against which it has been invoked by U.S. Presidents, was the grasping British empire, and that the Monroe Doctrine is a fundamental extension of U. S. constitutional law.

Great Britain had by no means given up hopes of expansion in the Western Hemisphere by the early 1820s, hardly a decade after the War of 1812.The United States had recognized the independence of Colombia, Peru, Chile, Buenos Aires (capital of what is now Argentina, then the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata), and Mexico, but Great Britain had recognized none. Pleased that the empires of Spain and France had been curtailed in the New World, the British still had by no means reconciled themselves to the end of colonialism—as their control of colonial Canada today underlines.

Yet in 1823 British Foreign Secretary George Canning made an offer to the United States which he believed it could not refuse. In discussions with U.S. Ambassador to London Richard Rush, Canning proposed a joint U. S.-British declaration to guarantee the emancipation of Spain’s colonies in the Western Hemisphere. The five-point declaration stated that Spain’s former colonies should not be recoverable by Spain, nor transferred to any other power, although it renounced claims by the authors to impede negotiations between Spain and the colonies or take possession themselves. Within this Wilsonesque rhetoric, however, there was one tell-tale omission: Rather than recognizing the former Spanish colonies as independent states, the Canning proposal said: “We conceive the question of the recognition of them, as Independent States, to be one of time and circumstances.”

John Quincy Adams—the statesman who represented the very best of the American System tradition inherited from his father, John Adams, and his mentor Benjamin Franklin—was the only principal in the Monroe administration not taken in by the Canning declaration. While President Monroe was receiving advice from former Presidents Jefferson and Madison to the effect that such a de facto alliance with Great Britain would be the best protection for the militarily weak United States, Quincy Adams launched a campaign for a unilateral U.S. declaration against all the oligarchical powers of Europe.

No Community of Principle with Britain

Quincy Adams, who was to be elected to the presidency the next year, had, throughout his service as a statesman, worked to strengthen America’s commitment to the spread of republicanism in Latin America. Even before the United States had recognized many of the continent’s new nations, Quincy Adams wrote:

The emancipation of the South American continent opens to the whole race of man prospects of futurity in which this Union will be called in the discharge of its duties to itself and to unnumbered ages of posterity to take a conspicuous and leading role…. That the fabric of our social connections with our southern neighbors may rise in the lapse of years with a grandeur and harmony of proportions corresponding with the magnificence of the means placed by Providence in our power and that of our descendants; its foundations must be laid in principles of politics and of morals, new and distasteful to the thrones and dominations of the elder world.

(Letter to Richard Anderson, U. S. minister in Bogota, Colombia, May 27, 1823.)

When Canning’s proposal reached his desk later in 1823, world events made clear to Quincy Adams the necessity of defending the principles of non-colonization, and non-interference in the Western Hemisphere by all the powers of the Holy Alliance. Russia was at the very same time in negotiations with the United States about lands it claimed along the Pacific coast in what is today the state of Oregon. France also had claims against Middle America.

On the face of it, Britain was the only one of the Holy Alliance powers willing to renounce colonization, and was the strongest of these powers in military terms. But John Quincy Adams argued that as long as Great Britain would not recognize the sovereign independence of the new nations in the Western Hemisphere, the United States could not even entertain the idea of signing a parallel declaration with the British, much less a joint declaration. He wrote:

So long as Great Britain withholds the recognition of that [independence], we may, as we certainly do, concur with her in the aversion to the transfer to any other power of any of the Colonies in this Hemisphere, heretofore or yet, belonging to Spain; but the principles of that aversion, so far as they are common to both parties, resting only upon a casual coincidence of interests, in a national point of view selfish on both sides, would be liable to dissolution by every change of phase in the aspect of European politics…. Britain and America … would not be bound by ‘any permanent community of principle.’

Adams’s concept of a community of principle was well-known among the proponents of the American System at the time, including the Marquis de Lafayette. It meant relations between states were to be based on mutual respect for national sovereignty, that sovereignty itself being defined not by mere brute exercise of power, but by the commitment to the betterment of its population morally and materially. Such a commitment to the principle of sovereignty demanded peaceful relations among states and stood in total contrast to the maneuverings for looting arrangements that characterized the relations among the European powers.

Thus John Quincy Adams wrote in his diary of Nov. 7, 1823 that an independent American declaration of support for republics of Latin America against the European powers was necessary because:

It affords a very suitable and convenient opportunity for us to take our stand against the Holy Alliance and at the same time to decline the overture of Great Britain. It would be more candid, as well as more dignified, to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France, than to come in as a cock-boat in the wake of the British man-of-war.

Promulgation of the Monroe Doctrine

President Monroe was won to Quincy Adams’s position. On Dec. 2, 1823, the Monroe Doctrine was promulgated, echoing the policy enunciated in the Federalist Papers and George Washington’s great Farewell Address, in which our first President warned of entanglements with the politics or controversies of Europe on the grounds that the United States as a constitutional republic must not subordinate its interests to those of the European oligarchies. The Monroe Doctrine extended this protection to all the nations of the hemisphere:

as a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are involved … the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers…. In the wars of the European powers in matters relating to them-selves we have never taken any part, nor does it comport with our policy to do so. It is only when our rights are invaded or seriously menaced that we resent injuries or make preparation for our defense. With the movements in this hemisphere we are of necessity more immediately connected, and by causes which must be obvious to all enlightened and impartial observers. The political system of the allied powers is essentially different in this respect from that of America. This difference proceeds from that which exists in their respective Governments; and to the defense of our own, which has been achieved by the loss of so much blood and treasure, and matured by the wisdom of their most enlightened citizens, and under which we have enjoyed unexampled felicity, this whole nation is devoted. We owe it, therefore, to candor and the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety.

Within a few years of Monroe’s proclamation, it had become a guideline for U. S. foreign policy. In 1825, President John Quincy Adams’s Secretary of State Henry Clay sent a set of instructions to Joel Poinsett, the U.S. minister in Mexico, directing Poinsett to bring the Mexicans’ attention to Monroe’s message “asserting certain important principles of intercontinental law, in the relations of Europe and America.” The first principle was that the Americas would no longer be considered subjects for colonization by European powers. The second principle, wrote Clay, is that “we should regard as dangerous to our peace and safety” any effort on the part of Europe “to extend their political system to any portion of this hemisphere. The political systems of the two continents are essentially different.”

In 1863, Mexican President Benito Juárez urged the United States to invoke the Monroe Doctrine against the attempts of the Swiss financial oligarchy to impose a monarchy on Mexico to guarantee the payment of that nation’s foreign debt. Under the London Convention of October 1863, the navies of France, England, and Spain, and more than 20,000 troops, had combined to mount an invasion of Mexico to revoke the Mexican government’s sovereign decision to impose a debt moratorium against those countries.

The weakness of the war-torn United States prevented Lincoln from going to the aid of his ally Juárez. There are numerous documents demonstrating that Lincoln’s strategy was to fight his battles one at a time, with this basic concern at that time being to safeguard the Union, and to neutralize British agents of influence, who, like his Secretary of State Seward, were working against him from within.

The Venezuela Dispute

In 1895, President Grover Cleveland invoked the Monroe Doctrine against Britain during the British-Venezuela boundary dispute concerning “British” Guiana. The British raised the objection that the Monroe Doctrine was incomplete and not a part of international law. Cleveland responded that the doctrine “was intended to apply to every stage in our national life and cannot become obsolete while our republic endures.” Cleveland added that the doctrine “has its place in the code of international law as certainly and securely as if it were specifically mentioned.”

At Cleveland’s instruction, his Secretary of State Richard Olney delivered a long message to the U.S. ambassador in London for transmittal to Lord Salisbury. The Monroe Doctrine, wrote Olney, applied the logic of Washington’s Farewell Address by declaring that American non-intervention in European affairs necessarily implied European non-intervention in American affairs.[[1]]

The rule is … that no European power or combination of European powers shall forcibly deprive any American state of the right and power of self-government and of shaping for itself its own political fortunes and destines. That the rule thus defined has been the accepted public law of this country ever since its promulgation cannot be fairly denied...

What is true of the material, is no less true of what may be termed the moral interests involved…. Europe as a whole is monarchical, and, with the single important exception of the republic of France, is committed to the monarchical principle. America, on the other hand, is devoted to exactly the opposite principle.

In the 20th Century

Although it is the case that British-influenced occupants of the White House and State Department in the 20th Century—especially Theodore Roosevelt—have more often applied the Monroe Doctrine in service of the financial interests of the European oligarchy, the spirit of James Monroe and John Quincy Adams’s original declaration was still alive in the April 19, 1939 speech of Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the Pan-American Congress.

The American family of nations pays honor to the oldest and most successful association of sovereign nations which exists in the world. What is it that has protected us from the tragic involvements which are today making the old world a new cockpit of old struggles? The answer is easily found. A new and powerful ideal—that of the community of nations—sprang up at the same time the Americas became free and independent…. The American peace we celebrate today has no quality of weakness in it. We are prepared to maintain it and defend it to the fullest extent of our strength, matching force to force if any attempt is made to subvert our institutions, or impair the independence of any one of our group.

Should the method of attack be that of economic pressure, I pledge that my own country will also give economic support, so that no American nation need surrender any fraction of its sovereign freedom to maintain its economic welfare. This is the spirit and the intent of the Declaration of Lima: the solidarity of the American continent….

The Roosevelt Corollary and the Drago Doctrine

In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt desecrated the Monroe Doctrine, reversing its intention entirely and giving it the negative reputation it holds today. While John Quincy Adams and his collaborators saw the United States as the defender of a “community of principle” among mutually equal and sovereign nation states, thereby necessitating its involvement to banish European colonialism from the Americas, Teddy Roosevelt saw the U.S. as an enforcer of European colonialism upon the Americas. In 1902, when Venezuela refused to pay debts imposed by European creditors, British, German, and Italian warships were sent to impose a military blockade on Venezuela, and even bombarded the country’s ports. Roosevelt’s response was not to defend Venezuela’s sovereignty or condemn the imperial overreach of European financier interests, but instead to allow the attack to proceed. After the conflict ended and Venezuela was forced to compromise, Roosevelt announced his new and updated version of the Monroe Doctrine.

In announcing the Roosevelt Corollary in a speech to Congress on Dec. 6, 1904, Roosevelt insisted that the most important rule between nations is that each “performs its duty toward others.” He said: “Any country whose people conduct themselves well can count upon our hearty friendship. If a nation shows it knows how to act with reasonable efficiency and decency in social and political matters, if it keeps order and pays its obligations [debts], it need fear no interference from the United States. Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power.”

If all Caribbean nations would show “progress in stable and just civilization,” Roosevelt went on, “all question of interference by this Nation with their affairs would be at an end.”

The Drago Doctrine

In contrast to this, Argentine Foreign Minister Luis María Drago (1859-1921) wrote a letter to his government’s ambassador in Washington at the beginning of the Venezuela crisis in 1902, and addressed the actions of the European colonial powers from a very different standpoint. He characterized his letter as “the financial corollary to the Monroe Doctrine,” a concept which has since been incorporated into international law as “the Drago Doctrine.” Below are excerpts from Drago’s letter.

It should be noted in this regard that the capitalist who lends his money to a foreign state is always aware of the resources of the country in which he is going to act and the greater or lesser possibility that the contract will be complied with without problems.

All governments, depending on their level of civilization and culture and their conduct in business matters, thereby enjoy different [levels] of creditworthiness, and these circumstances are measured and weighed before any loan is contracted….

The creditor is aware that his contract is with a sovereign entity; it is an inherent condition of sovereignty that executive procedures cannot be initiated or carried out against it, since that type of collection would compromise its very existence, causing the independence and action of the respective government to disappear.

Among the fundamental principles of public international law which humanity has consecrated, one of the most precious is that which determines that all states, regardless of the power at their disposal, are legal entities—perfectly equal among themselves and thereby, in reciprocity, deserving of the same consideration and respect.

Recognition of the debt and its liquidation can and must be carried out by the nation, without in any way undermining its fundamental rights as a sovereign entity; but, at a given moment, compulsive and immediate [debt] collection by force could only result in the ruin of the weakest nations and their absorption by the powerful of the Earth….

The principles proclaimed on this continent of America state otherwise. “The contracts between a nation and particular individuals are enforceable according to the conscience of the sovereign and cannot be the object of compulsory force,” wrote the famous [Alexander] Hamilton. “Outside of the sovereign will, they cannot be enforced.”

The United States has gone very far in this regard. The eleventh amendment of its Constitution establishes, in effect… that a nation’s judicial power cannot extend to any legal case or equity brought against one of the states by citizens of another state, or by citizens or subjects of a foreign state….

What it has not established, and what is by no means admissible, is that once the amount owed is legally determined, the right to choose the means and opportunity of payment cannot be denied the creditor … because the collective honor and creditworthiness [of all] are bound therein.

This is by no means a defense of bad faith, disorder, or deliberate or voluntary insolvency. It is simply a protection of the respect of the public international entity which cannot be dragged to war in this fashion, undermining the noble purposes determining the existence and freedom of nations.

The recognition of the public debt, the definite obligation to pay it, is not, on the other hand, an unimportant statement even though its collection cannot in practice, lead us onto the path of violence….

Your Excellency will understand the sense of alarm which has arisen upon learning that Venezuela’s failure to pay the service on its public debt is one of the reasons for the detention of its fleet, the bombardment of one of its ports, and the military blockade rigorously established along its coasts. If these procedures were to be definitively adopted, they would set a dangerous precedent for the security and peace of nations….

The military collection of debts implies territorial occupation to make it effective, and territorial occupation means the suppression or subordination of local governments in the countries to which this is extended.

This situation appears to visibly contradict the principles so often advocated by the nations of America, particularly the Monroe Doctrine, always so ardently maintained and defended always by the United States….

We by no means imply that the South American nations can remain exempt from all the responsibilities which a violation of international law implies for civilized nations. The only thing that the Republic of Argentina maintains, and what it would with great satisfaction like to see consecrated regarding the developments in Venezuela by a nation which, like the United States, enjoys great authority and power, is the already accepted principle that there cannot be European territorial expansion in America, nor oppression of this continent’s peoples just because an unfortunate financial situation could cause one of them to postpone meeting their obligations. In a word, the principle I would like to see recognized is that the public debt cannot give way to armed intervention, or a material occupation of American soil by a European power.

When the U.S. Invoked the Monroe Doctrine

by Mark Sonnenblick

• 1823: Monroe Doctrine proclaimed

• 1825-26: Bolivar’s Panama Congress

President John Quincy Adams, author of Monroe’s message, dispatched two delegates to a conference of American nations called in Panama by the British-run “liberator,” Simon Bólívar. Bólívar’s agenda would have made Spain’s former colonies into British protectorates, but the Monroe Doctrine aided Latin republicans to foil Bólívar’s plot.

• 1833: Malvinas Islands

The Monroe Doctrine was not invoked in response to the first major overt violation of its principles, because the traitorous administration of President Andrew Jackson was an active participant. In 1831, the U.S.S. Lexington reacted to Argentine efforts to enforce sovereignty over whalers operating in and around the Malvinas by physically devastating the Argentine settlement. Argentina broke relations with the United States and pressed fruitless claims for reparations. Secure they could mock the Monroe Doctrine with impunity, the British grabbed the battered “Falklands.”

• 1838: French Intervention into Mexico

France blockaded Mexico’s main port from 1837 to 1839 to collect debt claims. In 1838 the House of Representatives unanimously passed the resolution of Rep. Caleb Cushing (Mass.) quoting Monroe’s message and questioning “the ulterior views and designs of the French government with regard to the Mexican Republic.”

• 1838-45: British and French Blockade of Argentina

In 1838 British and French fleets jointly occupied the Plate River (in Argentina) to attempt to overthrow the Rosas government of Argentina and make Uruguay a British protectorate. The United States repeatedly protested in the name of the Monroe Doctrine.

• 1842-48: Texas

President Tyler’s 1842 message to Congress threatened “war between the United States and Great Britain” should Britain not stop its project for controlling the proxy republic of Texas. On Dec. 2, 1845, a statement by President Polk strongly reiterated the Monroe Doctrine and extended it to cover all “European interference” in the American republics. But Polk’s use of the Monroe Doctrine as cover for the expansion of slavery caused many in Congress to question its use.

• 1842-45: California

U.S. Commodore Thomas Jones briefly occupied Monterrey in the name of the Monroe Doctrine to preempt a British conspiracy to assure, in the words of British Minister Pakenham, “that California, once ceasing to belong to Mexico, should not fall into the hands of any Power but England.” The Monroe Doctrine was also invoked by Secretary of State Buchanan on the same question in 1845.

• 1844: Oregon

A House of Representatives committee report on British plans to extend Canada to Oregon stated that the Monroe Doctrine “has deservedly come to be regarded as an essential part of the international law of the New World.” President Polk stated, “Let a fixed principle of our Government be not to permit Great Britain or any other foreign power to plant a colony or hold dominion over any portion of the people or territory of either [American] continent.”

• 1848: Yucatan Indian Rebellion

From its colony in Belize, the British armed the Indians of Yucatan and encouraged them to rebel against the local government. The United States feared Britain could take over Yucatan and then Mexico. The United States intervened with military force to help crush the rebellion. Polk stated, “the transfer of dominion or sovereignty either to Spain, Great Britain or any other power” would not be tolerated under the principles enunciated by President Monroe.

• 1841-48: Mosquito Coast

In 1848 several Britons raised a crude Union Jack on the Caribbean coast of Central America and claimed most of that coast in the name of the “Kingdom of the Mosquito Indians.” In 1845, Nueva Granada (now Colombia) appealed for the United States to invoke the Monroe Doctrine, which it did in 1847 and 1848.

• 1861: Spanish Re-annexation of Santo Domingo

With the United States locked in civil war, Spain landed troops in Santo Domingo and declared the Dominican Republic again part of Spain. Lincoln’s representative in Spain, William Preston, protested, “There is no doctrine in which my government is more fixed than in its determination to resist any attempt of an European power to interfere for the purpose of controlling the destiny of the American republics or reestablishing over them monarchical power….” Preston later threatened Spain with war. Spain withdrew just as the Union won the Civil War.

• 1861-67: Habsburg Monarchy in Mexico

In late 1861, French and British troops landed in Mexico on the pretext of collecting debts. Lincoln immediately sent messages explaining the principles of the Monroe Doctrine to the European governments. Congress approved a resolution supporting the Monroe Doctrine as U.S. policy by a 109-0 vote.

• 1864: Spain Reclaims Peruvian Islands

On the grounds that Spain never recognized Spanish America’s independence, Spain seized Peru’s Guano Islands. Lincoln protested, leading to a Spanish promise to withdraw, not to recover any part of its former colonies, and to recognize the Monroe Doctrine.

• 1884: French Base in Haiti

Secretary of State Frelinghuysen objected to plans for Haiti to sell France a naval base on straits between Haiti and Cuba. France backed down rather than “expose us to confront the redoubtable Monroe Doctrine…. You shall not have, at least at this time, an occasion to apply it against us.”

• 1889: Pan American Conference

Secretary of State James Blaine finally fulfilled his dream of uniting the American republics for peace and mutual economic development. The Pan American Union continentalized the Monroe Doctrine and set up the framework for Organization of American States and the Rio Treaty of 1947.

• 1902: Calvo Doctrine

British and German gunboats attacked Venezuela and blockaded its harbor to collect debts. Argentine Foreign Minister Luis Drago extended the Monroe Doctrine, “a doctrine to which the Argentine Republic has heretofore solemnly adhered, to mean that the public debt cannot occasion armed intervention nor even the actual occupation of the territory of American nations by a European power….”

• 1904: Roosevelt Corollary

Teddy Roosevelt, a tool of the British Morgan bankers, responded that, in order to prevent European intervention to collect debts, “the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power….” Roosevelt thereby turned the Monroe Doctrine on its head. It has never recovered its original meaning.

[[1]]: Olney explicitly referenced Washington’s Farewell Address in his letter to Lord Salisbury, and even called the Monroe Doctrine the “doctrine of the Farewell Address.”