The name of John F. Kennedy will always be associated with the commitment made by the President in 1961 for the United States to send a man to the Moon and bring him back within the decade. This is rightly seen as the highpoint in the development of U.S. technology and a major event of the 20th Century—man’s first venture on another planet. While the planting of an American flag on the Moon is often regarded as the iconic symbol of that mission, people don’t realize that this might well have been an American astronaut and a Russian cosmonaut, with both planting flags on the Moon, indicating major reconciliation here on Earth between peoples. For Kennedy, in fact, a planned mission to the Moon was not merely an effort to exhibit American prowess in space, but a possible means of establishing his main goal—peace here on Earth—by achieving a reconciliation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

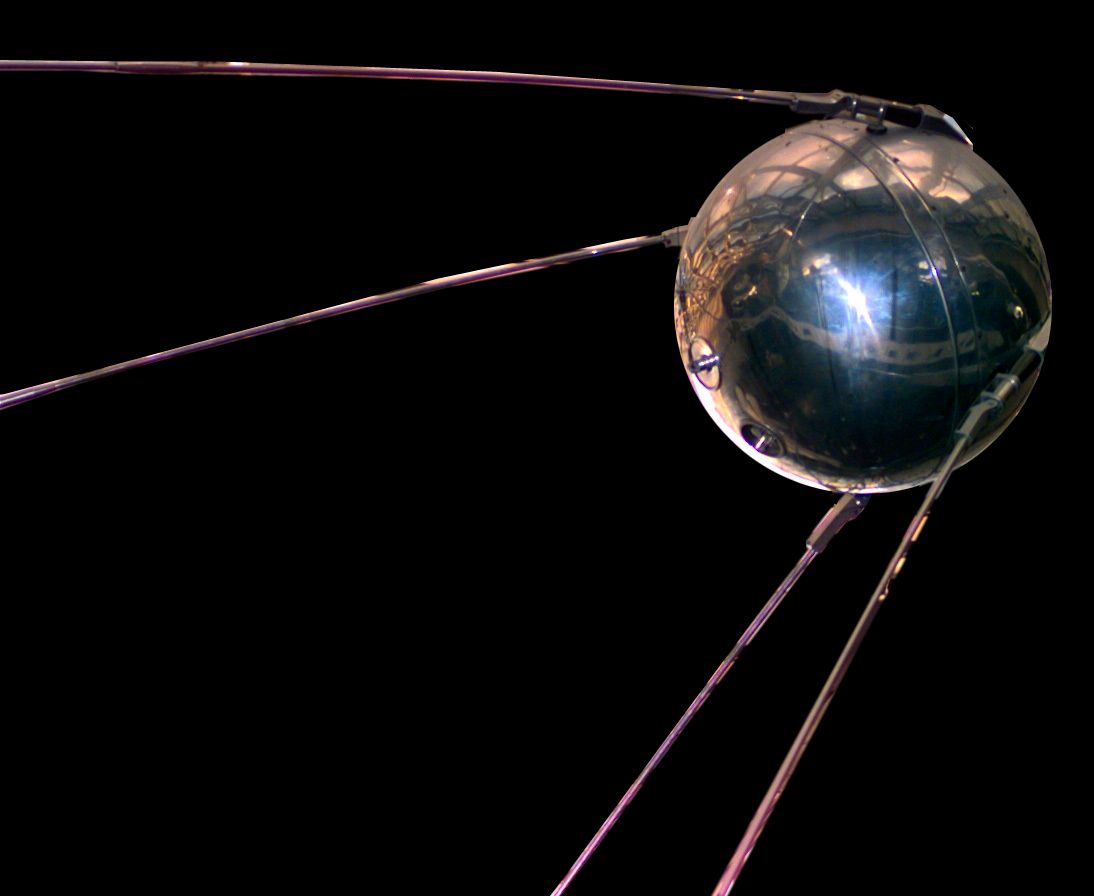

In one sense, the issue of space had been with Kennedy ever since his election as president. One of the key factors that may well have secured his victory (which was a close one) was his accusations against the previous Eisenhower Administration (and its Vice President Richard Nixon, his Republican opponent), for allowing a missile gap between the United States and the Soviet Union to develop. Some pundits claim that the accusation was something of a hoax. The U.S. was not really at a disadvantage to the Soviet Union in overall military terms. But the Soviets did have an advantage in rocket development. When both the United States and Russia developed nuclear weapons, the U.S. prioritized its bomber fleet for delivery of such weapons, as they had done at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Soviets prioritized delivery by the much more effective missile delivery systems.

Undoing the Cold War Agenda

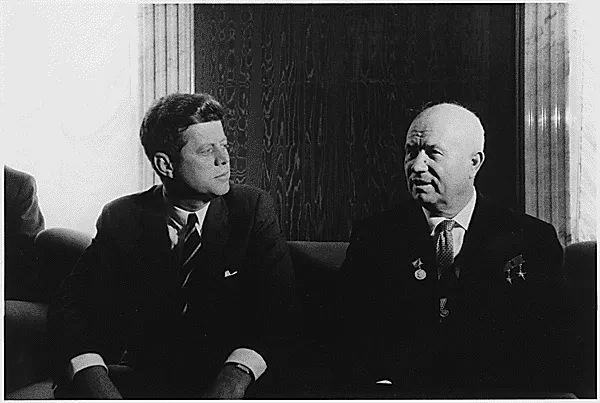

The major problem facing the new president was the relationship with the Soviet Union, a World War II ally, which, with the onset of the Cold War, had become our primary military rival. Kennedy wished to chart a path back toward the sort of cooperation that existed during the war years, in spite of the obvious ideological differences.

Already in his Inaugural Address on January 20, 1961, Kennedy gives an inkling of what he had in mind with regard to this issue. Referring to the conflict with the Soviet Union, Kennedy said:

Together, let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depth, and encourage the arts and commerce.

Even during his pre-campaign for President and earlier as Senator, in 1959, Kennedy had indicated the possibility of collaboration with the Soviet Union in space exploration.

One week after the Inaugural Address, in his State of the Union message on January 30, Kennedy was much more specific on the matter.

Finally this Administration intends to explore promptly all possible areas of cooperation with the Soviet Union and other nations “to invoke the wonders of science instead of its terrors.” Specifically, I invite all nations—including the Soviet Union—to join with us in developing a weather prediction program, in a new communications satellite program, and in preparation for probing the distant planets of Mars and Venus, probes which may some day unlock the secrets of the universe.

Today, this country is ahead in the science and technology of space while the Soviet Union is ahead in the capacity to lift large vehicles into orbit. Both nations would help themselves as well as other nations by removing these endeavors from the bitter and wasteful competition of the Cold War. The United States would be willing to join with the Soviet Union and the scientists of all nations in a greater effort to make the fruits of this knowledge available to all … to make our own laboratories available to technicians of other lands who lack the facilities to pursue their own work.

On February 15, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev responded to a telegram of congratulations which Kennedy had sent him on the successful launch of a Russian probe to the planet Venus. In his telegram, Khrushchev wrote,

In your speech of inauguration to the office of President, and likewise in the message to Congress of January 30, you, Mr. President, said that you would like for the Soviet Union and the United States of America to unite their efforts in such areas as the struggle against disease, mastering the cosmos, development of culture and trade. Such an approach to these problems impresses us and we welcome these utterances of yours.

On the U.S. side, a future U.S. lunar mission was already being discussed within NASA, but no decisions regarding such had been made. Then on April 12, the Soviets became the first to send a man, Yuri Gagarin, into orbit around the Earth. The successful launch sent official Washington into a tailspin. Kennedy sent a congratulatory letter to Khrushchev on the successful flight, again noting that the two sides could work together in space. At the same time, with the U.S. again upstaged by the Soviet Union, as it had been with Sputnik, he was desperately looking for some project that could restore U.S. leadership in space exploration. The idea of a lunar mission then suddenly went from backroom discussions in NASA offices to the Oval Office.

On April 14, Kennedy called in Hugh Sidey, a friendly Time/Life journalist, to attend an unusual pow-wow between Kennedy and his closest advisers on space, to discuss how the U.S. could respond to the Gagarin flight. The meeting included White House Press Secretary Pierre Salinger, Presidential Science Adviser James Wiesner, NASA Chief James Webb, and NASA Assistant Administrator Hugh Dryden. Sidey wrote about the meeting, noting Kennedy’s interest in probing the possibility of a Moon landing, thereby letting the public know that the President was focused on the matter. Then on April 20, Kennedy formed a Space Council and appointed Vice President Johnson to head it.