Dec. 26, 2024—Could “China and the United States … together solve all of the problems of the world—if you think about it” as President-elect Donald Trump suggested on Dec. 16?

Let us think about one huge problem they could collaborate to solve, and that is the tremendous burden of debt, and dearth of development credit, which has been holding back economic development in many “Global South” nations over the past five years—since the 2018-19 commodity inflation, COVID pandemic, central bank inflation, and then Federal Reserve interest rate spike.

In 2024 the burden of debt service on developing nations’ budgets was at an all-time high, at 42.2% of the total government spending of all developing countries. Sovereign lending for development projects is far behind, and at elevated interest rates. A Foreign Affairs piece of July 11, “Debt Is Dragging Down the Developing World,” notes that “when the Federal Reserve raised interest rates on U.S. Treasury Securities in March 2022, low-income countries’ currencies declined in value and their governments lost access to capital markets.” The 75 poorest countries are spending almost 8% of their entire GDP on debt service in 2024 (a total of $185 billion, or $2.5 billion for each of these poorest countries).

The Schiller Institute is circulating the most important, economically transformational development projects worldwide, in a pamphlet report released in early December, Development Drive Means Billions of New Jobs, No Refugees, No War. There are the problems of the world, to be solved by a United States working together with China, and cooperating with BRICS nations.

But first, the new American President will have to avoid the United States’ own debt crisis and the “Liz Truss effect” with which Wall Street and London are threatening him. If he tries big tax cuts and higher defense spending at the same time, as the then-incoming British Prime Minister did in September 2022, he could be hit with a government bond collapse like the one that dumped Ms. Truss out of office the very next month.

The crisis is a real one in the Treasury market, the world’s largest financial market and largest locus of derivatives speculation, with tens of thousands of speculating hedge funds who at times recently have threatened to “control” it. The national debt of the United States has grown by 50% in five years, and is on an unprecedented expansion approximating $2 trillion/year, projected into the 2030s. Federal spending has jumped as much in single years—for example, by $617 billion from Fiscal Year 2023 to 2024—as U.S. Federal tax revenue has risen in ten years—by $610 billion from FY2015-2024. Federal spending has been 25-30% of GDP in Fiscal Years 2020-24, compared to a 50-year average of 21% of GDP.

This, with no manufacturing boom, with productivity growth below 1.5% per year, and with little new housing being built. Average prices of American urban homes have also risen by 50% in the same five years.

In October and November 2024—the first two months of Fiscal Year 2025—the United States Federal budget was again in the red by a record amount by far, even compared to the last fiscal year’s riot of new debt. The United States was racking up new debt 65% faster than in Fiscal Year 2024.

The Federal Reserve Problem

The explosive domination of speculation in debt securities and derivatives in the United States’ commercial banking system, from the LTCM collapse of 1998-99 to the global financial crash of 2007-08, can be put down to the 1990s elimination of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 and its protective regulations and amendments. But the decade after the 2007-08 crash was dominated by the zero-interest, quantitative easing policy of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank (along with the central banks of Europe and Japan).

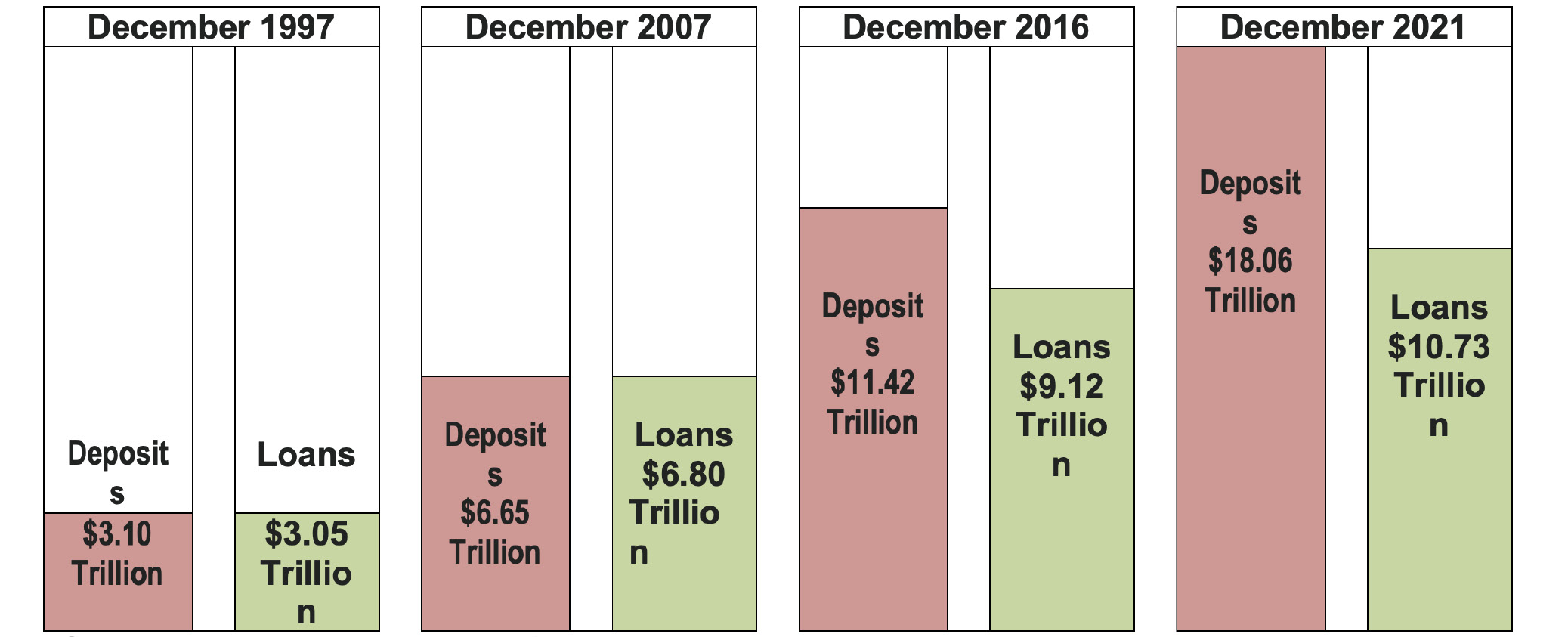

The Federal Reserve led other U.S. agencies in providing a total of approximately $14 trillion in new support to the financial sector, according to the June 22, 2011 congressional testimony of then-FDIC chair Sheila Bair. EIR has shown (Figure 1) that the biggest U.S.-based banks responded with stagnation in their lending to the economy, and concentrated on speculating with their floods of new deposits courtesy of the Fed.

American GDP growth during the Federal Reserve’s take-charge decade 2009-18, averaged just 2.2% per year. It was only the biggest banks that grew—by some 40% in deposits and assets.

The People’s Bank of China and China’s largest state-owned banks also, ironically, provided about the same $14 trillion equivalent in new currency to the Chinese economy in that decade. But by contrast, this was not used as excess bank reserves to back up vast financial speculations, but as credit to production and productivity: It generated, according to the estimates of PricewaterhouseCoopers’ annual reports on China’s economic expansion, some $10 trillion worth of new, tangible productive assets in industry and infrastructure, both in China and abroad through the Belt and Road Initiative.

China’s GDP growth over 2009-18 averaged 8% per year. China accounted for a third of world economic growth in the decade following the global financial crash of 2007-08. In that decade, when the Federal Reserve “took charge,” China emerged as the world’s leading economy in purchasing power GDP as well as manufacturing.

When the Federal Reserve’s money-printing finally triggered commodity inflation and then a 2019-23 general inflation which reached 9% even in the American economy; as the Fed then lurched from quantitative easing to a 2023 interest rate spike of more than 5%, China’s annual GDP growth—though slower—continued to double that of the United States. It became the world’s largest economy (on a purchasing-power parity basis), manufacturer, and merchandise trader.

‘Regime Change’

What has driven the debt crisis that now confronts the Trump Presidency, has been the 2019-2024 partnership of the Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury. It has been called, in central banking circles, a “regime change” in favor of the Fed; the Treasury, issuing $7 trillion in new debt, was made partner to the Federal Reserve issuing trillions in excess bank reserves and absorbing that new debt.

In the total $9 trillion money-printing “partnership” of Federal Reserve and Treasury since late 2019, it was actually then-Chair Janet Yellen’s Federal Reserve that plunged in first, months before now-Secretary Janet Yellen’s Treasury joined. During the “repo crisis” of interbank markets which surfaced on Sept. 15, 2019, the Federal Reserve Bank loaned, first billions, then tens, and finally hundreds of billions over every night for 18 days, through Oct. 3, 2019, to megabanks which in turn were lending to their own “traders” and to hedge funds and other speculating non-banks. On Oct, 4, 2019 this overnight lending became long lending: “QE5” (Federal Reserve quantitative easing program number-5), directly handing tens of billions in excess reserves to megabanks, which in turn created new, “liquid” bank deposits—printing money.

The Federal Reserve then combined with the Treasury in another huge wave of dollar printing and international liquidity lending beginning in March 2020, after the COVID-19 pandemic seized up value chains in many economies. In the United States, “special purpose vehicles” were created for the Federal Reserve and Treasury to finance or back “payroll protection program” loans, corporate jumbo loans and stock purchases, municipal bond purchases, state budget loans, and various pandemic benefits and subsidies.

Since then, tens of thousands of hedge funds swarm the near-$30 trillion public market in Treasury securities, buying short-term collateral for speculations. The Federal Reserve Bank provides the liquidity for this in the forms of “excess bank reserves” and “liquidity loans.”

U.S. banks have backed away from holding U.S. Treasury debt themselves, preferring to lend to hedge funds which speculate in the Treasuries and the Treasury derivatives known as “basis trades,” etc. Other major nations’ central banks and sovereign wealth funds have also reduced their holdings of U.S. debt. The Federal Reserve remains in the center of a vast speculation in that rapidly expanding debt by the financial sector.

As of the week ending Dec. 20, 2024, all banks in the U.S. banking system, combined, held roughly $1.6 trillion of U.S. Treasury debt securities, about 6% of their assets. As of the same week, the Federal Reserve still held nearly triple that, $4.4 trillion, which was well over half of its assets. The biggest banks have trillions in what are called “excess reserves,” gained by dumping U.S. Treasury debt, and private mortgage-backed securities, onto the Fed’s books. The big banks are being paid the full Federal Funds rate of interest for the reserves! (This is known as IOER, “interest on excess reserves.”)

Nationalize the Fed, ‘Glass-Steagall’ the Banks

The new U.S. Administration can see: Federal Reserve policy since the Global Financial Crash has done more than support a decade of economic stagnation and then two years of runaway inflation; since late-2019, it has supported the U.S. Treasury in the greatest flood of debt, deficit and general government subsidy in the history of any nation. United States credit is at risk.

Congress and the President should take action together. The Federal Reserve Bank should be nationalized: given a new, radically different charter, which mandates it to cease functioning as a reserve bank for big banks, and transforms it into a credit institution for the nation’s capital budget, and to stimulate capital goods exports for economic development.

A reserve bank’s primary function is to provide enough liquid reserves for the largest Wall Street, London, and European banks, supposedly enabling those megabanks to save the financial markets by providing liquidity to speculating entities whenever a crash threatens—no matter how dangerous the speculations, or huge those excess bank reserves may have to be.

(The other major central banks called “reserve banks” show it to be a British colonial holdover: The Reserve Bank of India, the South African Reserve Bank, the Reserve Bank of Australia, and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand.)

The primary function of a national credit institution is to provide credit to agencies carrying out the nation’s important capital projects; to assist the business lending of commercial banks to contractors on those projects, by “discounting” those private banks’ loans; and to contribute credit to multinational development banks which are helping fund projects of economic transformation in the rest of the world. This is a national bank, as the United States under the “American System” had national banking throughout most of the 19th Century, and again during the 1930s-1950s through the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.

If the present Federal Reserve Bank’s function as the primary safety-and-soundness regulator of nationally chartered commercial banks must continue, this residual function may continue through the District Banks of the new Bank.

But the current bank’s practice of setting short-term rates to “target inflation” or “ensure liquidity” should be ended by the new charter. Its practice of creating excess bank reserves for the big banks should be ended, as well as the practice of paying them interest for parking those reserves back at the Fed. Its current practice, during this past five-year period, of allowing private banks to set their required reserves at zero, should be banned.

The newly chartered national bank should be required to reduce its bloated $4.4 trillion holdings of Treasury securities as rapidly as possible to below $1 trillion, in the process allowing buyers of the Treasuries to convert them to capital in the new national bank—capital stock or debenture bonds. This will increase the new national bank’s credit capacity.

The Federal Reserve Bank’s current large holding of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) “assets,” and/or of other forms of derivatives should be banned under the new charter. These are the basis for much more speculation in the private banking system, in riskier mortgage debt derivatives. The Fed’s holdings of $2.25 trillion in MBS—hardly reduced in the past two years of supposed “tightening” of its books—have done nothing to aid the housing mortgage market, which is currently nearly frozen.

Prohibiting the newly chartered national bank from purchasing Treasury securities as collateral for “excess reserves” provided to the biggest banks (known as “quantitative easing” or “QE”), will prevent the Bank from guaranteeing a bailout of those banks’ speculations. It should therefore bring forward proposals to re-enact and re-enforce the Glass-Steagall Act regulations. These segregate the megabanks’ investment divisions and speculative securities operations so that they cannot be bailed out with taxpayers’ and depositors’ money.

Investment in Growing Productivity

The new charter should create a credit bank—a lending institution for agencies carrying out major projects of new infrastructure, and a discounting bank for private banks which are lending to manufacturers and constructors. The newly chartered national bank will still be the United States Treasury’s bank of deposit for Federal tax, customs, and other revenues.

As with the prior national banks in the history of the American System of economy, the new national bank will be able, by multi-year loans for infrastructure and manufacturing, to issue credit equal to a four- to five-times multiple of any Federal revenue allocated to it for purposes of those loans.

In other words, the United States will be able to operate a separate capital budget, administered through the lending authorities of the newly chartered national bank, which multiplies, by long-term lending, what the Federal government would otherwise spend on important missions and projects of new, high-technology infrastructure and physical-economic growth in industry.

A National Bank ‘To Create Wealth in the Form of Infrastructure’

The function of a new National Bank is provided here in excerpts from an article in EIR, Jan. 22, 1993 (Vol. 20, No. 4) quoting the late economist and statesman Lyndon LaRouche, founder of Executive Intelligence Review, in describing the operation of a national banking system creating national credit for economic development.

According to our Federal Constitution, the creation of money and the circulation and regulation thereof, is a monopolistic responsibility of the Federal government. The … President goes to the Congress and asks for a bill which authorizes the Executive branch to print and circulate money. Acting upon that bill, the President instructs the Secretary of the Treasury. And the proper procedure is that the Secretary of the Treasury issues the money. This money is then properly placed in a National Bank. It’s not spent usually for government expenditures directly. It’s not paid out by the government.

When it gets to the bank, it is loaned. The Federal government loans money, that is, its own created money, which it must not spend directly, generally, except in times of emergency…. Part of the money is used to be loaned, mixed with private savings and loans, to private companies for worthwhile kinds of private investments, categories of private investments, to build up the economy.

Loans for Productive Purposes

As detailed in the Federal Reserve Nationalization Act [of 1992—ed.], private banks would be able to get cash directly from the new National Bank only by bringing in a loan contract from a prospective borrower for a productive economic purpose, such as construction of a steel plant. The National Bank would provide up to 50% of the loan to the bank, charging the bank 2-4% interest. The bank would have to provide the rest from its deposits, and loan the total to the steel company at a regulated, low interest rate in the 4-6% range.

Perhaps 60% or more of this government money, however, “is loaned at low interest rates to government agencies such as state governments, state projects, or Federal corporations, corporations authorized by the Federal government, water project companies, or the Tennessee Valley Authority, for example,” LaRouche said. “These government companies use that money to create wealth in the form of infrastructure.” The Federal and state agencies which receive these loans “are like master contractors, which now borrow money from the National Bank at a 2%, 10-20 year term.”

The future increases in economic productivity that result from those projects will produce more new wealth than what is needed to pay down those capital-goods loans. This goes for capital-goods exports to other nations, particularly developing countries, as well for the capital budget of the United States.

Specifically, Congress by legislation will authorize the creation of a public corporation to be called the Bank of the United States; and it will authorize creation of a division within that Bank to operate a large capital budget, as the National Bank for Infrastructure and Manufacturing. This will be authorized to: provide credit for major national projects of infrastructure, including surface transportation and ports, national intercity electrified rail transport, water management and supply, drought prevention, flood prevention and storm protection, electrical energy production and distribution, and space exploration; make loans to agencies of the United States authorized for such projects; provide credit to state and municipal capital projects by purchase of municipal bonds as issued; and discount bank loans to businesses.

This Bank will also enter joint ventures with agencies of other nations, mutually to provide credit for major international projects of new infrastructure, including particularly in the developing nations. It will cooperate with the United States Export-Import Bank, and with the United States International Development Finance Corporation, to provide trade credits to businesses engaged in international infrastructure projects.

This is the necessary global policy for transformative economic infrastructure projects, laid out in the Schiller Institute’s pamphlet referenced at the beginning. It is the most effective way to stop the current mass flows of uncontrolled migration and associated drug trafficking.

The Global South will welcome this major addition to what the BRICS nations have been able to generate in development credit, mainly from China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Then China and the United States together can work on one avenue—economic and scientific development—to solve the problems of the world.